Thamer Hannona Sculpts the Future

From Concept to Concrete

By Cal Abbo

When ancient Mesopotamians carved their drawings into clay, constructed elaborate ziggurats and city gates, and designed practical and beautiful vases, their practice likely focused on their contemporaries. Thousands of year later, however, this act of creativity is kept alive by modern Chaldeans.

The long thread of Chaldean artistry has found its way to Thamer Hannona. While he expresses himself through many different media and inspirations, his car designs garner national appeal and the attention of large companies.

Thamer was born in Basra, Iraq in 1979, but didn’t live there very long. Before he was two years old, a massive war broke out between Iran and Iraq that would last the better part of a decade. Basra’s location on the border with Iran made it an easy target. His family moved to Kuwait, but not before his home in Basra was hit by an Iranian airstrike.

War followed the Hannona family to their new home. When he was 11 years old, his birth country, Iraq, invaded Kuwait. During that time, his family moved back to Iraq, then to Jordan, and finally made it to San Diego, California. He lived there for a few years before moving to Michigan in the middle of high school.

All of these transitions can be hard on some children, but Thamer seemed to flourish in spite of the change. By the time he moved to Michigan, he knew three languages fluently: Arabic, Chaldean, and English. Later, he would add a bit of Spanish and near-fluency in Brazilian Portuguese.

Until high school, art for Thamer was mostly a recreational activity that he enjoyed for its own sake. Later in life, he realized his passion came in a large sense from watching his father, Habib Hannona, create his own artwork.

Habib is a pioneer in the Chaldean community both in Iraq and Michigan. He is known as a jack-of-all-trades and has contributed to the world as an author, engineer, linguist, painter, poet, and much more. Perhaps most of all, Habib is famous for his historical work focusing on the history of Karamlesh, his home village, and his contributions to Chaldean history in general.

But in his free time, Habib likes to relax by working on art, and that had a heavy influence on Thamer, who gained an interest in drawing cars. “I thought I would be an engineer like my dad,” he said. “I had a scholarship to go to other schools for that. But my heart wasn’t in it.”

For many Chaldean students, this would be the end of the story. Their unique artistic contribution would remain a hobby and their talent would remain undeveloped. The pressure is on from their well-intentioned parents to join the professions or start a reliable business. But Thamer’s family was different, perhaps because his father experienced success in so many areas. Thus, his story continues.

“At Warren Mott, in 1996, my teacher gave me a hall pass to go and visit College for Creative Studies,” Thamer noted. “It was the senior show for the car design students. All of their work, including scale models, were on display.”

Thamer described this experience as a turning point in his own thinking, a realignment with what he considered possible. “It was like peeking into the future. I was instantly converted. It was love at first sight. That’s all I wanted to do since that moment,” he said.

After he graduated high school, Thamer worked hard to put together an art portfolio, which he had not much experience with before. He went to the admissions office and was eventually accepted. The program at CCS was intense and difficult, with many students dropping off in the middle because of the pressure or the cost. His first challenge was to pass his freshman year, which he said was a “tryout” for the real program, which, according to Thamer, ranks number 2 in the nation.

Thamer was behind his cohorts because he spent a semester getting caught up on other classes. Even as the dean told him he couldn’t make it into the program, he was accepted to the next three years of the car design program. Its exclusivity is justified by the lack of jobs available in that field. Only a few thousand people in the world get to design cars for a living.

There were 20 students in the program to start, but that drops all the way down to single digits in some cases. “I used to pull all-nighters once or twice a week,” Thamer claimed. “They want to make sure you’re fueled by passion.”

Thankfully, Thamer lived at home in Warren while he was studying. He claimed the entire basement as his workshop and had a scholarship to cover most of the costs; his parents picked up the remainder. At the end of his tenure, his story came full circle as he participated in the senior showcase, flaunting his car models. He made the list of almost all the companies that came to the show and had tons of offers from companies like Nissan, BMW, Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler. According to Thamer, GM was the most enthusiastic about him, and he saw a lot of growth opportunity in the company as they had many studios worldwide, so he took the job. That was 22 years ago.

“When I come to Detroit on business, I don’t even get a hotel. I just stay with my parents,” he said. “That’s how close it is. It’s crazy how close my parents live to the headquarters, like less than a mile. It’s serendipity, I guess. There are not many places to work, so very few people are from here. The car design community is very international.”

When Thamer designs a car, it takes about 2-4 years to reach production. His first design was one you’ll still see on the road today: the Chevrolet HHR, or “Heritage High Roof,” a retro-style five-passenger wagon modeled after the 1947-53 Chevy Suburban. The car has a classic feel with modern amenities. The HHR saw over 500,000 sales in its lifetime and, at its peak in 2008, ranked #36 in vehicle sales in the United States. Not bad for a first try.

The Chevrolet HHR, one of Thamer’s first car designs.

A large part of the car design business is patience and persistence. While Thamer finished this design before the end of 2003, it was still not produced and sold until 2005, and it didn’t gain serious traction until a year later. By then, he had moved onto bigger and better things. He was restationed in California at GM’s advance design center. “On the advance team, you work on things that are far term, the cars you’d see in showcases or auto shows,” Thamer said. Many of the projects he works on for the advance team are top-secret.

This was a quick move for someone who only joined the company in 2001, but Thamer actively sought out traveling and new experiences. He was only there for two years when he made a bigger move to Brazil. By the time he got there, the HHR, his first official design, was in its first year of production.

Thamer had long felt the pull of travel, and this experience helped scratch the itch. During the time he was there, Brazil was an emerging car market, and Thamer helped build GM’s design studio there with the ultimate goal of establishing a self-sustaining design community. “We had a low budget, so it’s a really different place than I was coming from,” he said. “We had to think more practically and cost-efficiently and in terms of production.” Often, Brazilian factories would receive leftover parts from Europe, which made for an interesting design challenge.

During his stay, Thamer lived in Sao Paolo, which was the third biggest city in the Americas after New York and Los Angeles, and has now surpassed both. GM gave him a bulletproof car. The office was far from where he lived, and driving in Brazil was nothing like he’d ever seen. “It’s the most dangerous thing you can imagine,” he said. “There’s a bunch of tight corners and turns and it’s very fast. I had serious anxiety every time I had to drive.”

Thamer loved the city culturally. “It was a big city, and there’s all these little pockets of beauty. You can drive about 60 miles to the beach too,” he said. “The food was the best part. Experiencing the barbecue for the first time was great, where they just bring you meat over and over.”

One of Thamer’s own contributions to Brazilian culture was the hookah. “I brought my hookah to Brazil and my friends were really into it,” he said. “I actually made some of my best friends there, people who are now lifelong friends.”

In 2007, Thamer officially moved to Los Angeles. One of his first projects was designing the famous Bumblebee Camaro in the fourth installment of Transformers movie franchise, called “Transformers: Age of Extinction.” The Camaros in past Transformers movies were facelifted Camaros that already existed, and the idea was to repeat that process. When Director Michael Bay was making the fourth movie, however, the sixth generation of Camaro was in development and still unavailable to the public, and Michael Bay wanted something new.

The solution was a 1 of 1 Camaro that Thamer designed in consultation with Michael Bay. Besides that one vehicle, that car did not make it into production. “I worked with the production designer and Michael Bay hand-in-hand to make it,” Thamer said. When it came out, the movie was top-15 grossing all time and has generated over $1 billion in gross revenue.

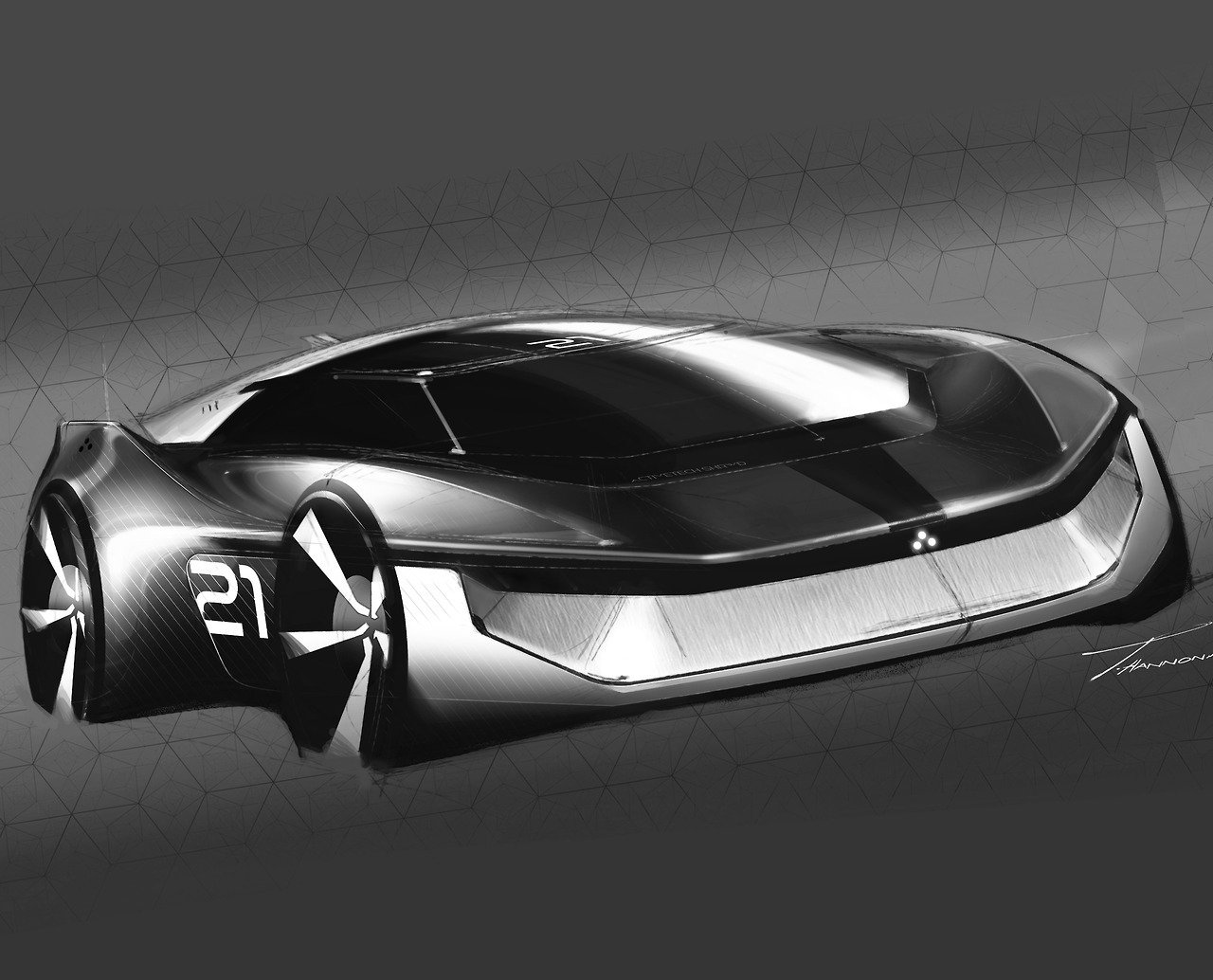

Now, Thamer leads a team of designers at GM. Because of his status on the advance team, most of his projects are secret and he isn’t able to talk about them in public. Recently, however, over the last few years one of his most compelling projects was released. Cadillac’s Halo Concept Portfolio certainly comes from the future.

The automotive industry is in the middle of two specific transitions that offer new challenges and ideas for Thamer and his team. First, demand for and efficiency of electric cars is constantly increasing, making them better alternatives to gas cars. For many reasons, it’s clear that this is the way of the future. The resulting mechanical changes to vehicles, like the lack of a combustion engine and the inclusion of a large battery, means that car designers need to dream up new ideas.

Just as well, autonomous driving is somewhere on the horizon, albeit a bit further away. The automotive industry currently has designated six levels of automation in vehicles. Most cars on the road function at level zero, where the operator is responsible for all braking, steering, and accelerating. Most new cars are level one, which means the car can apply brakes if you get too close to the car in front of you and aid with steering, like automatic lane assist.

Level two allows the driver to realistically disengage from operating the vehicle for an extended period of time, but it’s not quite reliable enough for the driver to take their eyes off the road. Right now, this is the most advanced technology that is commercially available. Tesla Autopilot and Cadillac Super Cruise both qualify as level two.

Levels three, four, and five describe high levels of automation that require almost no attention from the driver. At level five, which only exists conceptually, the car is not even equipped with any pedals, brakes, shifters, or steering wheels. These vehicles demand a complete interior redesign, since cars previously were designed around the necessity of pedals and a steering wheel. In addition, the passengers in a level five car now have to be occupied by something besides driving itself.

This shift requires intense creativity on the part of Thamer and his designers. The Cadillac Halo Portfolio is meant to showcase the first conception of a true level 5 automation. It consists of three vehicles, two ground-based and one quadcopter, that serve fully different purposes. The vision is that these cars are subscription-based. As a subscriber, you can schedule or call a vehicle when you need it and it will arrive to deliver you where you need.

These three vehicles compose the Cadillac Halo Portfolio: The PersonalSpace, SocialSpace, and InnerSpace.

The first vehicle, which looks like a massive drone, is called the PersonalSpace. “For high net-worth and busy people, time is the most valuable thing,” Thamer said. “You can do things in this vehicle without having to spend time driving. This will buy you time.” In addition, the three-dimensional nature of the quadcopter negates traffic and allows you to skip it altogether.

The second vehicle reminds one of a large van, and it’s called the SocialSpace. This is where you’d spend time with a large group of people. If you want to go out with friends, or if you have a business meeting, this is a great option. The interior of this space is designed in a style similar to a luxury limousine.

The third vehicle looks the most like a normal car. It’s called the InnerSpace, and it features a two-seater, sort of like a loveseat. “It’s sleek and low,” Thamer said. “There’s all kinds of biometrics readings and aromatherapy. Something that can teach you, enlighten you, and enrich you. The big challenge now is considering what you’ll do while you aren’t driving.”

The Halo designs are complex and forward-thinking. They require critical thinking and expertise that’s often underestimated. When Thamer started out, he loved to draw cars as a hobby, but that’s a far cry from designing them for actual production and commercial viability.

“Creating something from scratch, only with your mind, there was nothing I’d done like that before,” Thamer said. “It’s hard to teach someone how to design. You can teach someone how to draw, but the creative part comes from you.”

Thamer said he draws his ideas from many influences, and it’s hard to pinpoint a specific person or movement that shaped his thinking. He mentioned his high school and college teachers as well as a famous architect named Frank Lloyd Wright, who designed over 1,000 structures, including some houses in Bloomfield Hills. His most famous house is called Fallingwater, and he’s known for his organic style and holistic design. Even the furniture, according to Thamer, was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

“As a designer, you have to have a vision of how the whole thing fits together, even if you don’t have the expertise,” he said about Wright’s style and how he incorporates it into his own work. “In terms of car design, you’re trying to invent something new, so you can’t have too big of an inspiration.”

Thamer inside a prototype of the InnerSpace.

Thamer likes ideas that push boundaries, challenge existing norms, and open creative space. He understands the close interaction between peoples’ tastes, or what’s popular in the market, with trying to improve designs and push them further. “If you go too far, the people may not be ready for you,” he said. There’s a sweet spot that pushes the crowd ahead while also honoring what they already love.

Thamer still has dreams to pursue and not all of them have to do with his career. He enjoys spending time with his wife and kids, who have already become little artists themselves, especially taking them around the world to travel. Since he became a design team leader instead of a traditional designer, he took up cooking to spend some of his creative passion that he was bottling up.

“Just get good at something and practice it a lot,” Thamer said. In his own industry, there’s a lot of technology that can help a new designer cut corners, but he suggests avoiding that instinct. Embrace it, but make sure you do the groundwork, like sketching and ideation. This is a good lesson for any industry, most of which are being heavily disrupted by new technologies as we speak.

For younger people, according to Thamer, now is the time to take risks. “You have to dictate trends rather than be dictated by it. When you’re younger, you should take more risks because time is on your side, whether it’s investments, traveling, or living somewhere new.”