The Jewish Community of Iraq - History and Influence

by Adhid Miri, PhD

PART II – The Farhud and Exodus

In just a few decades of the 20th century, most of the Jewish communities - some with histories stretching back thousands of years - have been 'ethnically cleansed' from Arab countries. They fled not war, but systematic persecution.

Once an ally of Israel during the Shah years, the Islamic Republic of Iran is now acting as enemy. The number of Iranian Jews has fallen drastically, from 80,000 to about 20,000 since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

For centuries, Jews were well integrated into Iraqi society. Iraq was a generally a tolerant, multicultural society, with an Islamic majority composed of both Sunnis and Shiites, and significant Kurdish, Christian, and Jewish populations. From the late Ottoman period onward, as Iraq modernized, Jews formed an important segment of the middle and working classes—active in business, government, professions, academics, music, literature, and the trades.

In 1910, records show approximately 50,000 Jews living in Baghdad, roughly a quarter of the population of just over 200,000. By 1949, an estimated 130,000 Jews lived in Iraq, primarily in Baghdad, Basra, Hilla and Mosul. In the Kurdish region of Iraq, over 20,000 Jewish people lived in the villages and Kurdish towns such as Zakho, Aqra, Duhok, Amadiyya, Zibar, and Sulaymaniyah. Many immigrated to Israel in the early 1950s.

The Jewish community of Baghdad ran a variety of religious, educational, and social welfare institutions. Community documents provide a vivid and unparalleled record of Baghdad’s Jewish communal life from the end of the Ottoman era to the early 1970s.

As seen from the many locations mentioned in their corporate letterheads, prominent Jewish families in Baghdad established branches of their businesses in Britain, India, and the Far East. Maintaining their financial and familial ties with Iraq, they formed an international network in which Iraqi commerce was an essential component. The Sassoons and several other prominent Baghdadi Jewish families played an influential role in the development of business and manufacturing in Bombay, Hong Kong, Singapore, and elsewhere in the Far East.

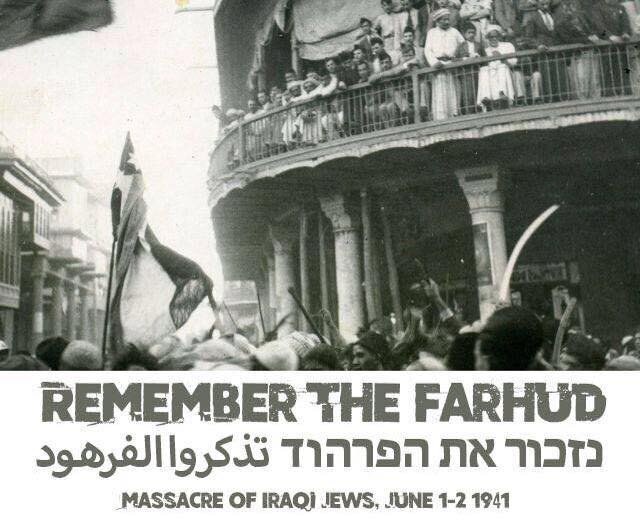

The Farhud

When the Iraqi State became independent in 1929, there was an increase in anti-Semitism, which accelerated after the appearance of the German ambassador A. Grobbe in Baghdad in 1932. In the days of the pro-Axis revolution of Rashid Ali Al-Gailani, riots against the Jews took place with the passive support of both the army and police.

The unraveling of Jewish life in Iraq began in the mid part of the 20th century, accelerating after the rise of Nazism in Germany and the proliferation of anti-Jewish propaganda. In June 1941, in the aftermath of the defeat of the pro-Nazi Iraqi regime, an anti-Jewish attack broke out in Baghdad during the Jewish festival of Shavuot. The unprecedented attack, known as the Farhud ("violent dispossession”) shattered the sense of safety and security of the Jews.

By this time there were approximately 150,000 Jews living in Iraq. Many of them worked in banking, commerce, government offices and farming. When the Farhud pogroms broke out immediately following the overthrow of the Rashid Ali government, which was inspired by the pro-Nazi Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the city of Baghdad was in a state of power vacuum.

The set of circumstances that allowed the pogroms included a combination of Nazi propaganda, including: the foundation of the “Al-Fatwa,” the Iraqi version of the Hitler Jugend (Youth); the influence of the Arab Revolt in Palestine; and the rage of the mob following the Iraqi defeat and heavy losses in the Anglo-Iraqi War.

Following the collapse of a short-lived pro-Nazi government and before British forces entered Baghdad, violent rioting ensued. From June 1 to 2, 1941, an estimated 180 Jews were killed, and hundreds were injured, while great numbers of Jewish homes and businesses were looted and destroyed. The most horrific acts of murder and rape were committed. Rioting mobs circled Baghdad neighborhoods armed with knives, axes, and firearms, some even carrying objects and furniture looted from Jewish homes. The murder victims were buried in a mass grave in Baghdad. There was also looting in many other cities at around the same time.

The Iraqi Jewish Farhud experience proved to be a turning point for the Jewish community. The Farhud, with its unprecedented anti-Jewish outbreak of violence, forever ended the comfort, safety, and continuity of Iraqi Jewry.

In 1945 there were frequent demonstrations against the Jews and especially against Zionism, and with the proclaimed partition of Palestine in 1947, the Jews were in danger of their lives. Many received harsh legal sentences and were forced to pay heavy fines. After the establishment of Israel in 1948, the practice of Zionism became a capital crime.

1948, the year of Israel's independence, was a rough year for the Jews of Iraq. In July, the government passed a law making all Zionist activity punishable by execution, with a minimum sentence of seven years’ imprisonment.

In August, Jews were forbidden to engage in banking or foreign currency transactions.

In September, Jews were dismissed from their jobs at the railways, the post office, the telegraph department, and the Finance Ministry on the grounds that they were suspected of "sabotage and treason.”

In October, the discharge of all Jewish officials and workers from all governmental departments was ordered and the issuance of export and import licenses to Jewish merchants was forbidden. To end the horrible year, in December the Iraq government suggested to oil companies operating in Iraq that no Jewish employees be accepted.

A major event occurred in September of 1948 when Shafiq Ades, a wealthy Iraqi- Jewish businessman of Syrian origin, was executed by hanging on charges of selling weapons to Israel and supporting the Iraqi Communist Party. He was born to a wealthy family based in Aleppo, Syria, and had migrated to Iraq and based himself in Basra.

Ades’ main business activity was the establishment and management of the Ford Motor car company agency in Iraq. He also partnered with a Muslim named Naji Al-Khedhairi in purchasing military metal scrap left in Iraq by the British army and selling the unusable parts after usable parts were sold to the government of Iraq.

In July 1948, Iraq made Zionist affiliation a criminal offense. When arrested, Ades was accused simultaneously of being a Zionist and a Communist. Ades accumulated business and personal ties with high-profile Iraqi notables and officials and even had accessibility to the regent Abdul Ilah. The Ford importer was by 1948 the wealthiest Jewish individual in Iraq.

With one historian calling it the "greatest shock to the Jewish community [of Iraq]," the execution of Ades had a profound impact on the Jewish community. Ades was both assimilated to Iraq and a non-Zionist Jew. The affair significantly reduced support for assimilation into Iraqi society and increased support for emigration as a solution to the crisis in the Iraqi Jewish community. There are streets in the Israeli cities that are named after Ades.

In 1950, the ban was lifted, and the Iraqi government issued an edict allowing the Jews to leave the country if they forfeited their Iraqi citizenship. The government of Israel, the Jewish Agency and the Joint Organization combined to carry out “Operation Ezra and Nehemiah,” in which 120,000 Jews were brought to Israel from Iraq. The edict decreed that each Jew of age ten and up could take a limited amount of money with them as they left. Many Jews were forced to leave their significant property behind for free.

One year later, the property of Jews who emigrated was frozen and economic restrictions were placed on Jews who chose to remain in the country.

In 1952, the Iraqi government closed the borders of the country once again and did not allow the remaining Jews to emigrate. Iraq’s government barred Jews from emigrating and publicly hanged two Jews after falsely charging them with hurling a bomb at the Baghdad office of the U.S. Information Agency.

Eleven years later, in 1963, the newly established Ba’ath government imposed further restrictions on the Jews. The sale of property was forbidden, and all Jews were forced to carry yellow identity cards.

In 1967, following the Six Day War, the treatment of Jews worsened. Some 3,000 were arrested and fired from their jobs, their bank accounts were frozen, Jewish-owned businesses were closed, trade deals signed by Jews were voided, and many telephone lines in Jewish homes were disconnected. Jews were placed under house arrest for long periods of time or restricted to the cities.

Persecution was at its worst in 1968. On January 27th of that year, scores of Iraqi Jews were jailed upon the discovery of the so-called local “spy ring” composed of Jewish businessmen. Fourteen men, eleven of them Jews, were accused of spying for Israel. The accused were put on staged sham trials, at the end of which some were sentenced and hanged in public squares in Baghdad while others died of torture. Due to international pressure, the Iraqi government allowed the remaining Jews to leave for Israel. As of 2014, there were only an estimated 60 Jews living in Baghdad.

Many Iraqi Jews felt rage and frustration at their loyalty to the state being doubted. Shalom Darwish, the secretary of the Jewish community in Baghdad, for instance, refused to renounce his Iraqi citizenship and chose to flee the country covertly. “I inherited my Iraqite’s from my fathers and grandfathers just as I inherited the blood in my veins,” he wrote. “I could not turn my citizenship into a piece of paper that you hand to a clerk to be put together with hundreds of others. My Iraqi citizenship was born thousands of years ago, before the grandfathers of those claiming to be Iraqis ever came to Iraq.” The Jewish community in Baghdad was founded in the mid-eighth century and from the 9th-11th centuries was the seat of the Exilarch (Resh Galutah)

The community continued to function to the extent possible from 1950 through the 1970s despite significant constraints. The recovered documents provide a vivid picture of the persistence of Jewish organizational life in Baghdad with the dwindling numbers of Jews and increasing insecurity. Jews and other minorities faced ongoing persecution following the revolution of 1958 and the rise of the Ba’athist Party in 1963, culminating in the public hanging of nine Jews in January of 1969.

In response to international pressure, the Baghdad government quietly allowed most of the remaining Jews to emigrate in the early 1970s, even while leaving other restrictions in force. Most of Iraq’s remaining Jews were now too old to leave. They had been pressured by the government to turn over title, without compensation, to over millions of dollars’ worth of Jewish community property. Only one synagogue continued to function in Iraq, “a crumbling buff-colored building tucked away in an alleyway” in Bataween, once Baghdad’s main Jewish neighborhood. Baghdad’s Jewish quarter, in Taht al-Takia, no longer exists.

The Jewish community had a presence in many Iraqi cities and provinces such as Hilla (Babel), A’anna, Rumadi, Duhok, and Erbil. In recent years, Jews in Iraq were permitted to live in two cities only – Baghdad and Basra. They numbered about 500 in total.

Operation Ezra and Nehemiah

From 1949 to 1951, 104,000 Jews were evacuated from Iraq in Operation Ezra & Nehemiah (named after the Jewish leaders who took their people back to Jerusalem from exile in Babylonia beginning in 597 B.C.E.); another 20,000 were smuggled out through Iran.

The number of Jews in Baghdad decreased from 100,000 to 77,000 and after the mass exodus to Israel. In 1968, there were only an estimated 2,000 Jews left in Iraq. With the establishment of Israel, hundreds of young Jews were arrested on charges of Zionist activity and two Zionist leaders were publicly hanged in Baghdad. On January 27, 1969, nine other Jews were hanged on charges of spying for Israel.

Iraqi activists still regularly charge that Israel used violence to engineer the exodus. The synagogue bombings of 1950 were such event. Iraqi nationalists threw bombs at Jewish institutions and synagogues in Baghdad, and Iraqi law forbade the Jews to leave the country.

From the start of the emigration law in March 1950 until the end of the year, 60,000 Jews registered to leave Iraq.

Two months before the expiration of the law, by which time about 85,000 Jews had registered, another bomb at the Masuda Shemtov Synagogue killed either 3 or 5 Jews and injured many others. While Israeli officials of the time vehemently deny it, historians report that "the belief that the bombs had been thrown by Zionist agents was shared by those Iraqi Jews who had just reached Israel.”

Iraqi authorities eventually charged three members of the Zionist underground with perpetrating some of the explosions. Two of those charged, Shalom Salah Shalom and Yosef Ibrahim Basri, were subsequently found guilty and executed, whilst the third was sentenced to a lengthy jail term. Salah Shalom claimed in his trial that he was tortured into confessing, and Yosef Basri maintained his innocence throughout.

Education

Until Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, there were 28 Jewish educational institutions in Baghdad. Sixteen were under the supervision of the community committee and the rest were privately run. The number of pupils reached 12,000; many others learned in foreign and government schools. An estimated 400 students studied medicine, law, economics, pharmacy, and engineering in these schools. In 1951, the Jewish school for the blind was closed; it was the only school of its type in Baghdad. The Jews of Baghdad had two hospitals in which the poor received free treatment, and several philanthropic services. Out of 60 synagogues in 1950, only seven remained in 1960.

The Alliance School (the Israeli Federation) is considered one of the oldest schools that provided service to the Israeli community in Iraq. It was established in 1864 and worked to allocate classes for teaching religious books to the Jews and preaching its concepts, especially the Talmud. It had always taught the Hebrew and Arabic languages, in addition to the general curriculum, and it is clear that the aforementioned school graduated caravans of young men, most of whom played a prominent role in Iraqi society.

Branches of the school were established in Mosul, Basra and Amara. In 1903, the Israeli Union Association established a school for girls' education in Baghdad, then in Basra, Mosul and Amarah. In 1921, construction was completed for the Laura Khadouri School for Girls, built by Azar Khadouri and named after his wife.

Education spread in Baghdad as the number of pupils enrolled in Jewish schools in Iraq reached 8,228 - distributed among only twenty-six schools in five Iraqi cities. Resources for the schools came from multiple destinations but most of them were the outcome of what the wealthy Jews donated in Iraq.

Jews in Israel

With Jews largely gone from Iraq, memories survive in Israel. Drive west to the shores of the Mediterranean - just a day’s journey geographically but a world away politically - and there is a lament inscribed at the entrance to the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Centre in Israel - “The Jewish community in Iraq is no more.”

It is no accident that such a somber epitaph to Iraq’s Jews should be found in Israel, where tens of thousands of them fled after 1948 amid the violent spasms that accompanied the birth of that state.

That transplanting of an educated, vibrant, and creative community unquestionably enriched Israel, but it also denuded Iraq of a minority that had long contributed to its political, economic, and cultural identity.

The creation of Israel in 1948 and its successive defeats of Arab armies caused further bursts of popular anger and violence against Jews, an episode of history that is written in graves in the cemetery, where five Iraqi Jews accused of spying for Israel now lie side by side.

Between 1950 and 1952 about 125,000 Iraqi Jews were airlifted to Israel. Each came with one suitcase, and all had to give up their Iraqi citizenship.

For one of them, Aharon Ben Hur, memories of Iraq are bitter. Now 84 and the owner of two falafel restaurants in Tel Aviv, he recalled the 1941 Farhud pogrom that killed more than 180 Jews during the Jewish festival of Shavuot. His father and younger brother were among them.

He left early, in 1951. Some hung on much longer. Emad Levy, 52, was the last of Baghdad’s Jews to immigrate to Israel, in 2010.

“We kept our tradition, the holidays, the synagogue,” he told Reuters during the build-up to Israel’s Independence Day. “But it’s not the joy you feel here during a holiday, walking down the street where most people are Jewish.”

Levy is among perhaps 600,000 Israelis, out of a population of some 8.8 million, who can claim a measure of Iraqi ancestry, according to the heritage center in the town of Or Yehuda near Tel Aviv.

Inside a building built in the style of a traditional two-story Jewish home in Baghdad, there are displays of religious and cultural artifacts of Jewish life in Iraq through the centuries. Visitors walk through the reconstructed crooked alleys of Baghdad’s Jewish quarter and view a scaled-down replica of the city’s Great Synagogue.

Exhibits at the museum depict a hard landing for the Iraqi immigrants in the early years of Israel, where Ashkenazim, or Jews of European descent, were the ruling elite and Sephardim, Jews with roots in the Middle East, faced prejudice.

But it also records how Iraqi Jews have gone on to become generals in the Israeli military, cabinet ministers, legislators, business executives, entertainers, and celebrated writers. Few expect ever to go back, amid the violent turmoil that still envelops Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and other countries which once had thriving Jewish communities.

“No one is going to move back,” concedes Shuker, 62, who had to escape Iraq in 1971. “However, there are many who would be very receptive to visiting their shrines and where their ancestors are buried. The Iraqi Jewish community is the most ardent Jewish community, probably anywhere, that is so attached to its birthplace, because of its history.”

Behind the high concrete walls of Baghdad’s Jewish cemetery, Violette Saul lies at rest under a weathered and cracked tombstone, one of the last memorials to an ancient community that is now all but extinct. The Iraqi nurse was buried a decade ago alongside thousands of others in the sands of a country where her community thrived for more than 2,500 years.

Iraqi Jewish life continues as a vibrant tradition in Iraqi Jewish communities worldwide. Rituals, language, recipes, songs, and literature flourish in synagogues, homes, and communal organizations. The carefully preserved books and documents discovered in the Iraqi intelligence headquarters in 2003 also help continue the heritage of Iraqi Jewry. Today, the 21st-century diaspora of Iraqi Jewry has a vitality and global impact reaching far beyond the “rivers of Babylon.”

This article is dedicated to preserving the memory of the near-extinct Jewish communities, which can never return to what and where they once were - even if they wanted to. Seen in this light, it is an expression of a common tragedy of oppressed indigenous, Middle Eastern people. The story is repeated in the 21st century as their fellow Christian, Yazidis, Mandeans and others struggle for recognition and restitution.

The plight of the Jewish community and that of all other communities (Christians, Yazidis, Mandeans) threatened by Islamism fall within the scope of this article content. Awareness of the injustice done to all these indigenous communities can only advance the cause of peace and reconciliation.

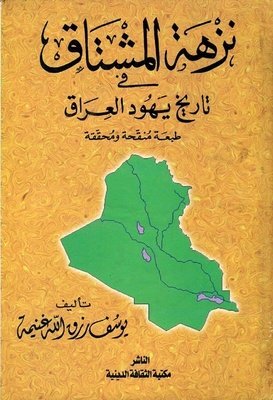

Acknowledgement of excerpts from Wikipedia and articles by Shamuel Moreh, Saad Salloum (Policies and Ethnicities of Iraq, Minorities in Iraq), Abbas Baghdadi (Baghdad in the Twenties), Mazin Lattif (Iraqi Jews), Yacoub Yousif Goreyh (The Jews of Iraq), Judge Zuhair Karim Abboud, Maher Chmaytelli - Jeffrey Heller - Stephen Farrell, Nostalgia Journey in the History of the Jews of Iraq by Yousif Rizq Allah Ghanima, and online interviews of Iraqi Jews by Kamal Yaldo. Special editing by Jacqueline Raxter.