Jesuits in Iraq: The Expulsion

By Dr. Adhid Miri

Part III

Because of their successful efforts in secondary education, the Jesuits had long considered an extension to the inviting field of higher education. Their motive was not to compete with the very competent and modern existing colleges in Iraq, but rather to encourage their Baghdad College alumni to remain in Iraq.

The attempt to provide higher education by sending the undergraduate abroad was not an adequate substitute for undergraduate education at home. Iraqi parents objected to uprooting a young person from their environment and planting them in the strange environment of an American or other foreign college, only to have them uprooted again upon return to their native land.

Permission granted

The Jesuits at Baghdad College were often encouraged by Muslim and Christian Iraqis to open an institution of higher learning. AI-Hikma University was not immediately approved by all Jesuits in the New England province because of the concerns of over-extension. The majority, however, regarded the foundation of AI-Hikma University as one of the most significant and far-reaching steps ever taken by the New England province; its existence was seen as tremendously important.

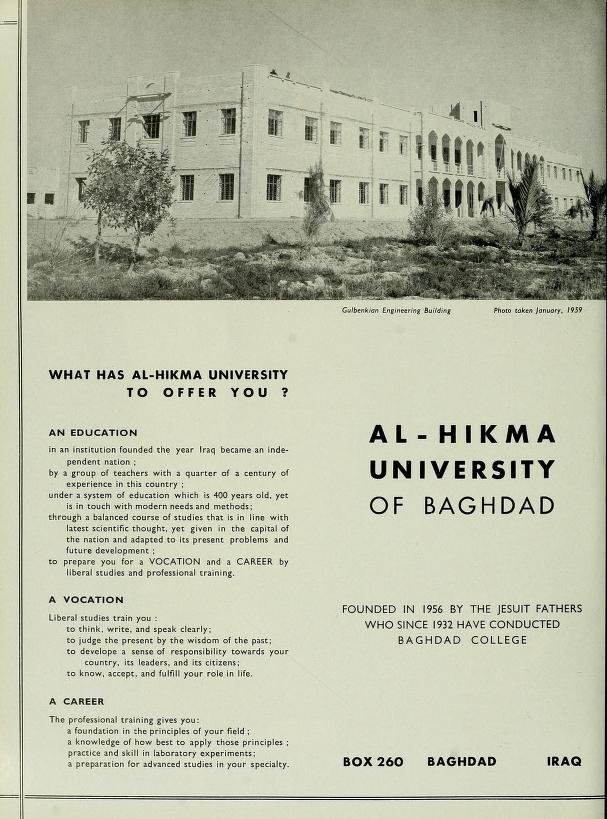

It was decided then to approach the Iraqi government on this matter, requesting permission to start a university and requesting land to build upon. Without objections, on May 5, 1955, the Ministry of Education gave permission for the opening of AI-Hikma University offering two four-year courses - one in Engineering Physics, and the other in Business Administration.

These two courses were chosen due to Iraq’s urgent need of engineers and administrators. Using two separate decrees, in 1955 and in 1956, the government of Iraq gifted the University 272 donums (about 168 acres) of land in Za’afarania, a suburb in the southernmost part of Baghdad. This land was about 14 miles by road from Baghdad College, which was in the northernmost part of the city. This gift was a striking testimony to the high esteem in which the Jesuit work at Baghdad College was held.

The confidence which the Iraqi government had in the Baghdad College Jesuits is dramatically shown in a sequence of efforts supporting them in their new venture. Fr. Hussey requested land, and without delay a 544 donum piece of government land (one donum is 2,500 square meters) in Za’afarania was designated and divided. It was on the Diyala River, 2.4 miles east of the Tigris, 3 miles north of the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala Rivers, and 14 miles south of Baghdad College in Sulaikh.

With the first grant, the Jesuits were to receive 200 donums (500,000 square meters or 125 acres). Additionally, the Iraqi government allowed the Jesuits to choose which part of this site they preferred. The Jesuits chose a plot so that most of the property would lie close to the main highway and would have a narrow (20 meter wide and 2 miles long) corridor running down to the Diyala River. The property widened out at the river so that they could install a pumping station.

On February 18, 1956, the title deed was finally drawn up by lawyer Khalid Isa Taha. This first land grant, Royal Decree #785, was backdated to September 10, 1955. Later, another adjoining 72 donum plot (44 acres) was requested and received according to Royal Decree #230, which was dated March 19, 1956, bringing the total area to 272 donums (168 acres).

This was a remarkable subsidy for the Jesuits when one considers that the Sulaikh property which they purchased in 1934 consisted of only 25 acres. At the time, the gifted land was worth about a half million dollars.

Fr. Hussey later asked the government to assist him in acquiring financial aid from United States agencies and he received full government cooperation. This was an impressive acknowledgment of the Iraqi’s high esteem for the work of the Jesuits in Iraq. The earliest and most crucial gift, these two generous land grants which the Jesuits requested, were mentioned in the official government publication, The Iraqi Gazette. It was signed by Prince Zaid, “Acting in place of the King.”

As highlighted in a letter by H.E. Nouri el-Said, Prime Minister of Iraq, to the Near East representative of the Ford Foundation, recommending aid for the university project of Baghdad College:

“On May 5th, 1955, the Iraq Minister of Education gave Baghdad College permission to begin courses of higher education in business, science, and engineering. On September 10th, 1955, a Royal lrada (decree) was signed which granted Baghdad College 500,000 square meters (about 124 acres) of land to be used for educational purposes.

Thus, the Government of Iraq has shown its interest in the part played by Baghdad College in the education of Iraqi youth.

We understand that Baghdad College has presented the Ford Foundation with a request for financial help. It is a request for 431,100.00 Dollars to enable Baghdad College to build on the above-mentioned property and to hire suitable professors for the education of their Iraqi students.

We take this occasion to recommend their request for your consideration. We feel sure that whatever help you give to Baghdad College will be used for the welfare of our nation through the proper education of our youth. Yours Sincerely, Nouri el Said.”

As a result of this intervention, the Ford Foundation Overseas Division contributed $400,000 for four buildings: the Business Administration Building, the faculty residence, cafeteria, and library.

Other sources provided generous assistance for the erection of the property buildings on the new Za’afarania campus. The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation of Lisbon provided $140,000 for the Engineering Building. The Ford Foundation contributed an additional $200,000 through the Sacred Congregation for the Oriental Church and the Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Another important grant included $110,000 for the purchase of equipment from the U.S. Department of State in conjunction with the Point-Four Program. The Jesuits submitted requests for financial help from other Jesuit schools as well.

AI-Hikma

The naming of AI-Hikma was not done precipitously as noted in Fr. Hussey’s letter to the N.E. Pr.: “I put aside any purely religious names on the recommendation of our sympathetic Muslim friends. This included the rejection of Jesuit University. I do not think that the Government would allow us the name Iraq University when their own is to be called Baghdad University, it would look as though we were above them. I did hesitate over the name Babylon University but there is that difficulty that Babylon has not a savory reputation in history and, especially in the Exercises of St. Ignatius. If it appeals to you over in the U.S., I would be very willing to reconsider it. We searched around for other names, traditional names of Baghdad like Al-Zawra or “Dar al-SaÂlaam” (now the name of an Adventist hospital here) but each had its own difficulties.

AI-Hikma can serve as the basis of our putting the university under the patronage of the Spirit of Wisdom or of Our Lady, Seat of Wisdom. It had these religious associations for us and yet for the Muslim it is still appropriate for a center of learning.”

When AI-Hikma began operating in September 1956, its total (freshman) enrollment was 45; within eight short years the enrollment had grown to 530. By the time the Jesuits were expelled, the enrollment had grown to 656. The student enrollment steadily increased, but the number of Jesuits actively engaged in administration and teaching did not grow as rapidly.

In November 1957, ground was broken at Za’afarania for the first building. By September 1959, the Engineering and Business buildings were completed. During AI-Hikma’s first three years at Sulaikh, the Jesuit architect, Fr. Leo Guay, was busy with the construction of the buildings which he had designed for the permanent Za’afarania campus. In the summer of 1958, the historic July 14 Revolution toppled the monarchy, and Iraq became a republic. Anxious days followed. The country underwent sudden and violent changes.

Building AI-Hikma went serenely on, and Fr. Guay quietly continued his construction work, so that by 1959 the campus moved from Sulaikh to Za’afarania. For nearly a year, the pioneering Jesuit community occupied interim quarters on the second floor of the Business Building, temporarily slept in classrooms, ate their meals in an unfinished laboratory, and depended on solar heating for their hot water. The following year they finally settled down in the spacious residence, Spellman Hall, designed and built by Fr. Guay.

This new campus, with assistance from Fr. Loeffler and his Iraqi gardeners, became one of the most attractive sights in the city. The enrollment, slow in the beginning, made rapid strides, and the facilities were taxed to the limit. As in Baghdad College, the athletic program and the wide and varied offering of activities made for a pleasant and relaxed atmosphere. AI-Hikma alumni who entered business or pursued graduate studies testified to the academic excellence of the university.

At the Za’afarania campus the first graduation was held in June 1960. Major General Abdul Karim Qasim, the Prime Minister of the Republic, delivered a talk and presented the diplomas. More than 1000 people attended; among those present were the chief officers of the new revolutionary government and members of the Diplomatic Corps.

AI-Hikma quickly attained a certain academic, moral, and social stature which made it a positive influence for good in many ways. It enjoyed a high reputation in both governmental and non-governmental circles, for academic excellence, integrity, and service. If this were not so, AI-Hikma would not have survived the situation which resulted from the June 1967 war between Israel and the Arab states. At that time emotions ran high, and a singularly bitter wave of anti-American feeling swept the Arab world and filled the Arab media.

In response to American support of Israel, AI-Hikma became the special object of attack by certain “concerned” writers in some Baghdad Arabic newspapers, and was alleged to be an enemy of the Arabs, a nest of spies and agents of the CIA.

The Iraqi government was called upon to take over AI-Hikma and Baghdad College. Throughout that anxious summer AI-Hikma benefited from the support and encouragement of many responsible Iraqis, in official as well as unofficial quarters. Applicants for registration were as numerous as ever, in fact AI-Hikma began the 1967 academic year with a substantial enrollment increase with 66 students over the previous year.

The Expulsion

Ignatian education, which began in 1547, is committed to the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement. Because of this, both Jesuit and lay educators in Jesuit schools have been a thorn in the side of tyrants for more than four centuries. Jesuits were often dismissed from countries and frequently involved in awesome controversies.

Such is the skeleton history of the Jesuits in Baghdad. They were not missionaries in the classical sense of the term, and they rarely preached at all. Baghdad was referred to by some as a fruitless waste of men and money; others called it a mission of faith to underline the lack of concrete consolations and accomplishments. But these were the judgments of “outsiders,” people who had not experienced the myriad fascinations of Baghdad and Baghdadis. They had no knowledge of the impact Jesuits made on students as well as their families, Muslim as well as Christian.

Jesuits also impacted Baghdad society. The opportunities provided to make contributions in education were many and the response of the Jesuits was praiseworthy. The development of an English program especially geared to Arabic speaking students was one instance; a course in religion tailored to Iraqi Christians was another.

Most fascinating was the case of Fr. Guay, who turned his side interest in architecture to a full-time occupation. He designed and executed the construction of most of the buildings on campus. The two Jesuit campuses were designed as low cost, functional architecture reflecting the periods of Iraqi history from Babylon up through the Muslim period. The Jesuit impact certainly went beyond the walls of the two schools.

It is hard for a foreigner to blend fully into a different culture, but the attempt was made and was appreciated. Fr. Richard McCarthy became one of the well-known Arabic preachers in the Christian community and established a reputation for his education in Muslim theology among the learned men in Iraq.

Perhaps it can all be summed up by the fact that the Iraqis are a happy and hospitable people, frank, warm, and forthright in expressing appreciation as well as disapproval.

The Jesuits had overcome, in part, their foreign origin and had identified with the church in Iraq and with the Iraqi educational system. However, there was always the awareness that at any time the Jesuits might be asked to leave as they were guests of the Iraqi government. Each year they had to renew their permits for residence in Iraq, and every wave of anti-American feeling which blew across the Middle East was a threat to their continued existence.

It was enjoyable to work in Baghdad although there were problems, springing mostly from the limits which came from being a foreigner. The Jesuits could serve the Christian poor, but the Muslim poor were beyond their reach. The Jesuits tried to foster social responsibility and be cautious not to enter the area of politics.

Iraq’s public and private education started shifting after the 1958 coup that overthrew the constitutional, pro-western monarchy, and has been in decline ever since, with competing philosophies about testing and methods falling in and out of favor.

Meanwhile, Jesuit education from 1932-1958 and during the turbulent years 1959-1968 maintained its consistent stance based on faith and integrity, educational rigor, and character building.

The revolution of 1958 and each subsequent revolution was a crisis of sorts. Each succeeding government studied the question of “foreign” schools; every time, Baghdad College and AI-Hikma University were judged beneficial to the country and their work went on - until the traumatic crisis of June 1967, when the Israelis took over Arab territory and displaced more Palestinian refugees. The wave of anti-American feeling reached new intensity because of the United States’ stance in the area, and it became clear that the continued presence of American Jesuits was more tenuous than ever.

For a time, it seemed that the Jesuits would weather this crisis as they had prior crises. School and work went on for another year, until a new revolution brought to power a socialist government interested in controlling all private education.

The government decreed that it would run the administration of AI-Hikma while the Jesuits continued to teach. The Jesuits accepted the proposal and attempted to work in the new framework, at least for a few months until an extremist element in the government decreed their expulsion from Iraq in November 1968. A year later, the American Jesuits at Baghdad College were ordered to leave by the same group.

The Jesuits left behind their modest monument - a secondary school, a university, some thousands of graduates, a handful of Iraqi Jesuits, and a wealth of good will and love. To be uprooted so quickly and curtly without explanation or excuse was not easy. Several of the sixty Jesuits expelled in 1968-1969 had spent over twenty years in Baghdad and had thought of nothing of living, working, and even dying in the country. By simple decree, those plans were voided.

That war of 1967, which was supposed to solve the problems of the area, only increased them and spawned new ones. The world took sides after so many years of neutrality, and the Jesuit College and University, which had seemed to blend into the surroundings so well, now became a foreign element in the eyes of some Iraqis. The years of devotion, service, and proven sympathy could not negate the origins of the Jesuits. And so, the Jesuits were sent off as quietly as they had arrived.

The expulsion was a disappointment and a shock of sorts, but it was not unexpected, it was a constant possibility during the 37 years the Jesuits worked in Iraq. All things are passing and the usefulness of the American Jesuit contribution to Iraq was nearing its end.

It is difficult for a foreigner to play an active role in the process of politicization and nationalization now gripping so many of the developing countries. Without regretting the past or prejudging the future, the Jesuits think the time has come for new forms and different accents.

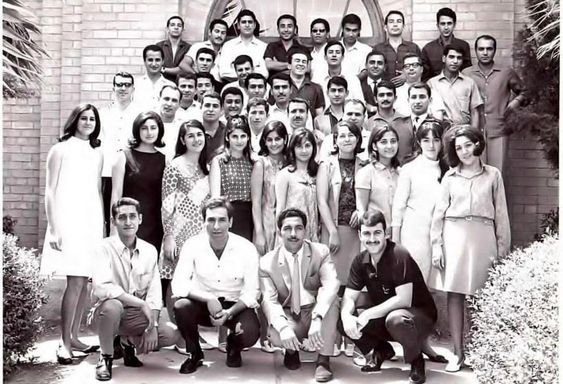

Legacy Reunions

Over the past years, many Iraqi graduates moved to America, Canada, and Europe and have held ten extraordinary reunions with their former Jesuit teachers, the most recent of which attracted 1,400 people. Reunions of graduates of both Baghdad College and Al-Hikma University continue to be held bi-annually.

At these gatherings, graduates discuss how they can pass on to their own children the system of values they have received. They appreciate the fact that the quality of their lives has been enriched. Their compassion for others has deepened and they value the spiritual dimension of life. The major concern of these men and women, some of whom are now American citizens, is how to serve others.

Injustice and loss of an educational opportunity

The Jesuits went to Baghdad in 1932 and started two large schools, Baghdad College and Al-Hikma University, where Christians and Jews worked, studied, and played together harmoniously.

Although initially suspicious, the Muslims came to admire the Jesuits for their dedication and persistence. They were impressed that the Jesuits held their posts during the short-lived pro-Nazi occupation of Baghdad during World War II and during the 1967 June war with Israel when the American Embassy closed and all other Americans fled.

In both cases, indeed over that 37-year period, the Iraqi people supported and encouraged the Jesuits in their educational work. The support of these warm and generous Iraqi people contrasted with the indifference toward the Jesuit work displayed by our own American Embassy in Iraq.

In 1968, the Baathi coup d’état brought about the demise of the Jesuit schools. The Baathi socialist party moved quickly, closing not only the Jesuit schools but also all private schools in Iraq, just as the Syrian Baathi government had done a decade before.

The only ones to come to the defense of the Jesuits were the Iraqi Muslim professors from the University of Baghdad. They pleaded in vain with Iraq’s new Baathi president: “You cannot treat the Jesuits this way: they have brought many innovations to Iraqi education and have enriched Iraq by their presence.”

Nevertheless, the Baathi socialist government ordered the Al-Hikma Jesuits out of the country in November of 1968. Hundreds of students came to the airport to bid them farewell, despite threats to their well-being that were indeed carried out by Baathi party members.

In August of 1969, the Jesuits of Baghdad College were also banished from Iraq. Both schools were taken over and all fifteen major buildings, including two libraries and seven modern laboratories, were confiscated by the Baathi party.

The most interesting part of the Baghdad Jesuit adventure does not concern buildings or huge campuses but concerns rather the students, their families, the Jesuits, and their colleagues. It was the people involved who made the mission such a happy memory, since there was much interaction between young American Jesuits and youthful Iraqi citizens and their families.

Much more than other Jesuits in their American schools, the “Baghdadi” Jesuits entered the family lives of their students frequently and intimately through home visits, celebrated Muslim and Christian feast days as well as myriad social events together, both happy and sad. Jesuits found the Iraqi students warm, hospitable, humorous, imaginative, receptive, hardworking, and appreciative of educational opportunities. The Iraqis found the Jesuits happy, fun-loving, intelligent, and dedicated.

In the recent past, great attention has again been paid to the Baghdad mission by the New England province, who made major investments of manpower, money, equipment, and prayers.

After the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, some Iraqis asked, “When are you Jesuits returning to Baghdad?” The sad fact is that of the original 145 Jesuits, few are still alive. Likely Jesuits from some province certainly will return because a place so important to Islam as well as to Christianity cannot be ignored for very long.

Reflecting on their work over the past 37 years, the Jesuits feel it was all very worthwhile and they are grateful to the many benefactors who made their work possible. It was an investment of men and of money in the process of human development. The yield has been great if one measures results in terms of human growth, love and understanding.

The Jesuits may have vanished from Iraq, but still have no closure. They have been trying to keep landmarks of their former lives in Iraq, arguing that their memorabilia is of historic interest and huge value to the rest of the Iraqi people. While Iraqis themselves are increasingly acknowledging the selfless loyalty of the Jesuits, the blocking of their return to Iraq rubs salt into the wound, adding yet another injustice to a very long list.

What form the future mission will take? We leave it to the Holy Spirit, who took the Jesuits to Baghdad in the first place. One thing is clear — the Jesuit mission to Iraq that ended in 1969 was a great loss to Iraq, its younger generations, and its educational system.

The history of the Jesuit mission in Iraq has been chronicled by the Rev. Joseph MacDonnell, S.J., late of Fairfield University, in his book Jesuits by the Tigris.

Special editing by Jacqueline Raxter and Dave Nona.