Traditional Chaldean Weddings

By Dr. Adhid Miri

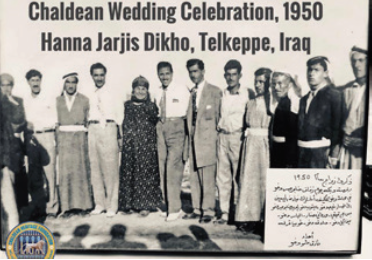

To reflect and connect with the past, it is necessary to shine a spotlight on the marriages that took place in the old farming villages in the Nineveh region of Iraq. Marriages often took place at a young age, usually thirteen to fifteen. The young groom would be assigned a marriage counselor (“Serdouch” or “Ustatha”/ leader or expert teacher) very early in the preparation steps, to in due course be taught the art of love.

A newlywed couple would live with the groom’s parents and grandparents, who had the ultimate say in everything. There was no dating those days and all marriages were prearranged by the parents. After agreeing to the terms, the groom family would visit the bride frequently to present her with gifts which almost always included a gold cross. Most people were poor farmers and could not afford a dowry. The dowry (“Urkha”) was equivalent to 100 Dinars (three hundred dollars) and was demanded by the bride-to-be’s family.

On occasion, the poor groom would offer two chickens and a rooster as a token of his love, hence coining the term, “He is worth two chickens and a rooster.”

Weddings took place early in the day on a Sunday in the spring or summer in the village. On the wedding day, in route to the church, the groom, his parents and his relatives would go to the bride’s home on foot in a big procession. The men were in the front followed by the women, singing and sounding (“Halahil”) accompanied by the Zarna and Tabul band.

One of the favorite parts of the wedding traditions, the blocking of the doorway, is managed by family members of the bride as the bride and groom are exiting the bride’s house. A few young men would block the bride in her bedroom and stand guard to block the door, insisting on getting paid in order to allow the bride to leave her family’s home.

Typically, a male family member from the bride’s side, in this role of the “bouncer,” is the bride’s brother, cousin, or younger male relative. Sometimes there is only one bouncer and other times there are a few who partner together to get the job done.

As for who pays up, this is dependent on the family. Sometimes the groom will pay off the bouncer, other times it’s the best man, and other times it’s another family member from the groom’s side. The bride will come out dressed in white and walk in front of the ladies toward the church for a ceremony that requires two witnesses.

After the ceremony the groom’s sisters and relatives, along with the bride, invite families and friends to the festivities at the groom’s house. On the way from church to the groom’s house, the celebrants go through the town streets and stop in every corner to sing, drink and dance to the tunes of the Zarna and Tabul. Villages were small and everyone participated in the festivities. Neighbors stood at their doors with a tray of sweets, jugs of cold water and a bottle of Arak (a traditional homemade drink) ready to pour. When the wedding group passed a home whose family had experienced a recent tragedy or loss of a loved one, the dancing and music would stop out of respect.

Before the bride and groom could enter their new home, they had to offer the men in the neighborhood a chicken and two bottles of Arak. The bride would be paraded around the village sitting on a decorated horse (the limo of those days) with a child sitting in front and one behind her. Her gifts and wedding accessories (“Jihaz”) were mounted on a second horse with a little girl astride, led by an older man. They included pillows, blankets, mattresses, bed sheets, and dresses among other items.

The wedding festivities lasted four days, with parties every night. On the last night, a large pot of Piqoota and chicken was served, signaling to the guests that it’s time to go home. The guests would sing the finale: “Fill and fill our bottles and cups…today we drink, tomorrow you kick us out.”

On one special occasion, a judge from Mosul (The Honorable Ahmmed Al-Awqati) was invited to a prominent wedding in the village of Telkepe. This was his first experience with such festivities and hewas asked to join the village priest and family procession to church. He was unaccustomed to the amount of drinks consumed along the way and told his son (and my life-long colleague), Dr. Mamun Al-Awqati, that by the time they reached the church he was drunk, the deacon was drunk, the groom was drunk and above all, the village priest was drunk. (The groom was none other than a Southfield Manor veteran, Faraj Sesi.)

Few things have changed since then, and many similar festivities continue in the United States. Chaldean weddings are notorious for always being a great time. From dancing all night to the delicious midnight snack, these weddings never cease to amaze.

In the Chaldean culture, there are several events and traditions surrounding the actual wedding ceremony and reception. First, before any church ceremony, one tradition that is very common is that the family of the groom goes to the bride’s house to “bring her” to her soon-tobe husband. What happens during this time is both families dance in the house and streets, surrounding the bride with joyful vibes.

The party starts at the bride’s house which is filled with food, drinks, music, dancing, and photography. A traditional folklore band called “Zarna & Tabul- Pipes & Drums” typically plays music during much of the party at the bride’s home. This band will also accompany the wedding party as they leave her home and head to the limousine.

This pre-wedding party usually lasts around two hours, with everyone taking pictures with the bride. Of course, the most important part of any Chaldean wedding, besides the amazing reception, is the Catholic Church ceremony. After the party at the bride’s home, guests will head to the church for the wedding ceremony (“Burakha”) with a priest. The religious ceremony that seals the couple’s bond is extremely important in Chaldean culture. Typically, the church that is chosen is one that either of the families has attended over the years, although this is not always the case.

A Chaldean wedding ceremony is filled with beautiful songs and prayers to celebrate the joining the bride and groom in the sacrament of marriage. The priests sing traditional Chaldean songs and say prayers in Aramaic before eventually speaking the vows and asking the bride and groom to say, “I do.”

A golden crown is placed on the bride and groom’s heads during the wedding ceremony, signifying their Chaldean traditions. The cere mon ial crowns represent Christ and the Church and the equality in their relationship – you need one to preserve the other.

You will also see the Kalilla (white bow) tied to the groom’s arm at the reception. This bow signifies that the groom is taking leadership as the head of his family. The Church ceremony typically lasts for approximately one hour.

Photography is a big part of the occasion. A humorous incident occurred during one Chaldean wedding when the best man went missing. Messages were repeatedly announced by the band over loudspeakers requesting him to join the wedding party for photos. After several announcements, a gentleman stepped up and squeezed next to the groom, posing for the historic wedding party photo. The photographer, puzzled by the presence of this gentleman intruder, asked him, “Sir, why are you here?” The confident intruder replied, “You have been calling me all night, my name is “Basman!”

It is both an American and a Chaldean tradition that the bride, groom and wedding party are introduced as they enter the reception celebration hall. The Arabic Zeffa is part of a tradition that makes it more fun and festive, and has evolved to include the cutting of the wedding cake. The characteristic Chaldean wedding reception usually commences rather late, around eight in the evening. To start the party, the entire bridal party is introduced during the Zeffa. Once guests have settled into their seats in the banquet hall, the bridesmaids and the groomsmen enter the venue as couples.

Typically, each wedding party couple will dance their way into the banquet hall as guests cheer them on. The couples will continue cheering and dancing until the entire wedding party has entered the reception gathering.

After all the wedding party has entered, everyone in attendance will head to the dance floor to celebrate the newlywed couple by dancing and singing for about a half hour or so before heading back to their tables.

You’ll never go hungry when attending a wedding at a Chaldean banquet hall! To start, the tables are filled with an array of delicious appetizers. Wedding food is always plentiful for guests. Once the guests are fed, it’s time to hit the dance floor for the rest of the night.

It’s imperative that all the guests help celebrate the newlywed couple by singing and dancing with them on the dance floor. While slower songs are sometimes played, the music tends to stay upbeat with a quick tempo so that the energy stays up.

The bridesmaids and groomsmen play an important role in the reception. Part of their responsibility is to make sure that the dance floor is always full, and the party doesn’t stop. If the members of the wedding party are on the dance floor celebrating, it entices the guests to stay on the dance floor to celebrate as they dance to traditional Chaldean Khugga music.

Usually around dinnertime, the newlywed couple will make their way around the banquet hall to greet their guests. Since most of the guests will be at their tables eating dinner, this is the ideal time for the bride and groom to say “hello” and thank them for being there. At this point in the celebration, everyone’s legs are most likely very tired from all the dancing, but there remains a buzz in the air from all the excitement and celebration. As every Chaldean knows, exiting out of a wedding celebration can take forever. Chaldeans are known for having very lengthy goodbyes.

Once you decide it’s time to leave, it may take another twenty to thirty minutes before everyone has said their goodbyes and hugged each other; along the way, there’s always someone urging you to stay and keep partying. It’s a long process, but the love shown to each other makes it all worth it. By the night’s end, participants are completely exhausted.

Weddings in general are extremely costly. Hosts spend a large amount of money on venues, food, and entertainment. To make their weddings extravagant, Chaldeans spend an obscene amount of money to impress their guests. During the wedding, instead of presenting gifts to the groom and bride, it is a tradition to gift money, because it is understood to be more useful than gifts, and to purchase what is needed. Gifting money is called “Sabahiyya.”

As a guest at a Chaldean wedding, it will probably take a long time to recover from the excitement. This celebration is the most important day in the life of a couple, and you just witnessed a night they will remember for the rest of their lives. The one thing you feel during these weddings is the love radiating out from the bridal party to everyone. It is amazing how these traditions have remained intact, and goes to show how strong the Chaldean community is. We continue to encourage our sons and daughters to marry within the Chaldean community and to celebrate with the traditions of our culture. There’s no wedding like a Chaldean wedding.