The Jewish Community of Iraq- History, Influence, and Memories

By Dr. Adhid Miri

Part I – The History

Memory binds people together, gives them a shared history and a memory. Without a shared history, people feel no sense of a place or identity. The Chaldean and Jewish communities have a long history of shared places and memories and were confronted with the same challenges and moral questions as the original citizens of modern-day Iraq. The two original ancient communities of Babylon shared contemporary and historical experiences through their geographical belonging to the region of Mesopotamia. The two minority communities shared a journey of hopes and disappointments based on integration and national consciousness.

In Baghdad-Iraq multi-cultural society of the twentieth century, the two communities were intertwined and lived together in old neighborhoods, spoke a similar “Mosuli” dialect and many had common names like (Dawood, Yousif, Ibrahim, Ya’acob, Murad, Moussa, Naiem, Salim, Salman, Naji). It is not a surprise that the journey binds the two communities again as they live side by side in Oak park, Southfield, and West Bloomfield in Michigan.

The chronology of Jews in Iraq stretches back some 4,000 years to the biblical patriarch Abraham of Ur, and to the Babylonian monarch Nebuchadnezzar, who sent Jews into exile there more than 2,500 years ago. Iraqi Jews constitute one of the world's oldest and most historically significant Jewish communities.

Babylonian rulers such as Nebuchadnezzar ruled the known world, and one word from them sufficed to move armies from place to place. Jerusalem was always an attractive occupation target. Upon the destruction of Jerusalem, a new phase began in the history of the People of Israel such as the exile of Babylon, which is of course in modern-day Iraq.

In 539 BCE the Babylonian Empire officially ended, when the city of Babylon itself fell to the Persian Empire, headed by King Cyrus. One of his first acts following this conquest was to issue the famous Proclamation of Cyrus, which granted freedom of religion to all peoples of the empire and granted the Jews autonomy in the Land of Israel. The residents of Babylon continued to enjoy prosperity even under the new rulers, and only some 50,000 Jews returned to the Land of Israel. Historian, Josephus Flavius noted that the Jews of Babylon were “Tens of thousands untold, their number beyond count”.

When the Babylonians conquered the southern tribes of Israel and enslaved the Jews, these Jews distinguished themselves from Sephardim, referring to themselves as Baylim (Hebrew for Babylonians”), immigrants and descendants of the immigrants of the Iraqi Jewish communities, who now reside within the state of Israel. They number around 450,000. In later centuries, the region became more hospitable to Jews and it became the home to some of the world's most prominent scholars who produced the Babylonian Talmud between 500 and 700 BCE.

The Jewish lunar calendar is strongly linked with the millennia of Jewish life in Babylon. The names of the months on the Jewish calendar originated from the ancient Babylonian calendar. A fixed calendrical calculation was finalized in the 10th century, largely by Saadia Gaon (882-942), the head of the renowned Talmudic academy of Sura.

For generations, the celebration of festivals has shaped the patterns of Jewish life. In this region where Jews lived for thousands of years, the political rulers changed frequently—from the Sassanians of the Talmudic era through the various leaders of the 20th century, yet the calendar cycle repeated itself each year, marking continuity for families and community.

Like the Jews of in modern times, the Jews living back then between the Euphrates and the Tigris supported their brethren in the Holy Land. Proof of the solidarity between the Jewish communities of Babylon and Judea can be found in the writings of the Jewish-Egyptian philosopher Philo, who claimed that one of the reasons that prevented the Governor of Syria from placing an idol in the Holy of Holies in the temple in Jerusalem was fear of the reaction by the Jews of Babylon. Jewish prophets and sites in Iraq are second to the Holy land.

The Jewish community of what is termed in Jewish sources "Babylon" or "Babylonia" included EZRA the scribe, whose return to Judea in the late 6th century BC is associated with significant changes in Jewish ritual observance and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Iraqi Jews lived in a land that was physically and culturally linked to the central sacred texts of Judaism. Babylonia in Ancient Mesopotamia is imbedded in biblical lore. According to Jewish tradition, the Garden of Eden was in the fertile region between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Iraqi Muslims and Iraqi Jews both revered local sites of tombs associated with biblical leaders and prophets, such as Daniel, Ezekiel, Ezra, and Jonah.

Jews in Iraq have ancient holy sites, they include more than 9 holy shrines that Jews historically made visits to when on holiday and at other times. Some of these shrines are also sacred to Muslims such as Ezekiel (thou Al Kifil). Above his tomb entrance, the tiles carry a Hebrew inscription that says: "Here is the tomb of our master Ezekiel."

The most famous shrines of the Jews are:

1 - The tomb of Ezra the priest, 2 - Ezekiel the Prophet, 3 - The shrine of Joshua Cohen Kadol, 4 - The tomb of Sheikh Isaac al-Qawuni, 5 - The tomb of Nahum al-Quoshi, and these shrines are taken by believers from this congregation to bless and seek the intercession of the prophets and the righteous.

The Iraqi government has refurbished the tombs of Hezekiel the Prophet and Ezra the Scribe which are also considered sacred by Muslims. Jonah the Prophet’s tomb has also been renovated. Saddam Hussein (also-remove) assigned guards to protect these holy places during his reign. Each year, hundreds of Muslim pilgrims’ flock to the holy sites to pay homage to these prophets.

In the last few years, USAID and American donations were used to restore the tomb of prophet Nahoum in the Northern Chaldean town of Alqoush in Nineveh province.

The Babylonian Talmud was compiled in “Babylonia”, identified with modern Iraq.

In the centuries after its compilation in the 5th century, it became the core text of Judaism combining traditional legal precedents, major Jewish concepts, and Jewish mores and practices. Renowned for their Jewish scholarship, the great 6th to 11th-century academies of Sura and Pumbedita elevated Babylonian rabbinic Judaism to become the dominant approach throughout the Jewish world.

During the tenth century there were two distinguished Jewish families in Baghdad, Netira and Aaron. At the end of the tenth century R. Isaac B. Moses Ibn Sakri of Spain was the Rosh Yeshiva. In the 12th century the Exilarch Daniel B. Chasdai was referred to by the Arabs as “Our Lord, The Son of David”.

The Baghdad community reached the height of its prosperity during the term of office of Rosh Yeshiva Samuel B. Ali Ha-Levi, an opponent of Maimonides, who raised Torah study in Baghdad to a high level. R. Eleazar B. Jacob Ha-Bavli and R. Isaac B. Israel were Rashei Yeshivot during the late 12th century through the middle of the 13th century.

In the late 18th century, the Jewish community of Baghdad began to recover. In 1774 there were 2,500 Jews living in the city, about 3% of the city's population. By 1893 the Jewish numbers had risen significantly, to about 50,000 souls (constituting approximately 35% of the city's population), and the number of synagogues rose from 3 to 30.

This demographic growth was reflected in the community leadership as well. The hereditary leadership which prevailed prior, headed by a “community president”, who always belonged to one of the most powerful families in the city and conducted reciprocal relations with the authorities to solidify position, died out.

From the second half of the 18th century through the beginning of the 19th, Turkish rule deteriorated and the attitude to the Jews became harsh. Many wealthy members of the community fled to Persia and other countries, among them David B. Sassoon, who moved his business to India. At that time 6,000 Jewish families were residents of Baghdad led by a Pasha, known as “King of The Jews”.

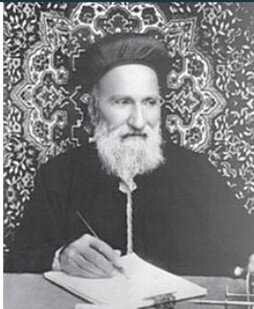

With the opening of the Suez Canal (1869) the situation of the city’s 20,000 Jews improved – along with the general economic situation – and many Jews from other localities settled there. In 1884 there were 30,000 Jews in Baghdad and by the beginning of the 20th century – 50,000. The greatest of the Baghdad Rabbis, Rabbi Joseph Hayyim Ben Eliahu Mazal-Tov (1834 – 1909), never accepted public financial assistance. His name is famous in the Jewish world, especially among the Baghdad-version (of prayer book) communities in Israel, England, India, Singapore, Manila etc.

During the 19th century, the influence of the Jewish families of Aleppo of the previous century faded as Baghdad emerged as a strong Jewish and economic center. The Jewish population had grown so rapidly that by 1884, there were 30,000 Jews in Baghdad and by 1900, 50,000, comprising over a quarter of the city's total population. Large-scale Jewish immigration from Kurdistan to Baghdad continued throughout this period. By the mid-19th century, the religious infrastructure of Baghdad grew to include a large yeshiva which trained up to sixty rabbis at a time. Religious scholarship flourished in Baghdad, which produced great rabbis, such as Joseph Hayyim ben Eliahu Mazal-Tov, known as the Ben Ish Chai (1834–1909) or Rabbi Abdallah Somekh (1813-1889).

Notable personalities in the 18th and 19th, Abdallah Somekh, who founded a rabbinical college, Beit Zilkha; R. Sassoon B. Israel; Jacob Tzemach; Ezekiel B. Reuben Manasseh; Joseph Gurji; Eliezer Khadhoori; and Menachem Daniel. Until 1849 the community of Baghdad was led by a president (“Nasi”), who was appointed by the vilayet governor, and who also acted as his banker. The most renowned of these leaders were Sassoon B. R. Tzalach, the father of the Sassoon family, and Ezra B. Joseph Gabbai.

Worthy to note the first Hebrew printing press in Baghdad was founded by Moses Baruch Mizrachi in 1863. Other printing presses were run by R. Ezra Reuben Dangoor and Elisha Shochet. A Hebrew weekly, Yeshurun, of which only five issues were published, appeared in 1920. This was the last attempt at Hebrew journalism in Baghdad.

From the end of the Ottoman period until 1931 there was a “General Council” of 80 members, among them 20 rabbis. A law was passed in early 1931 to permit “non-rabbis” to assume leadership. Despite this, in 1933, R. Sassoon Khadhoori was elected and in 1949 Ezekiel Shemtob succeeded him. Khadhoori returned to his position in 1953. In December 1951, the government abolished the rabbinical court in Baghdad.

During these centuries under Muslim, the Jewish Community had its ups and downs. By World War I, they accounted for one third of Baghdad’s population. In 1922, the British received a mandate over Iraq and began transforming it into a modern nation-state.

Until the British occupation of World War I, the Jews suffered from extortion and the cruelty of the local authorities. Many young men were recruited into the army to serve in the dangerous Caucasus mountains. With British entry to Baghdad on February 3, 1917, there began a period of freedom for the Jews of Baghdad and many of them were employed in civil service.

The Jewish community enjoyed economic prosperity and its leaders took a place in the textile and cotton trade with the British, who controlled these markets. In the first half of the 19th century Jewish families began to establish trading and entrepreneurship colonies outside of Baghdad as well, in the great cities of South- and East Asia – Hong Kong, Calcutta, Bombay, Singapore, Shanghai and others.

The immigrants established communities of “former Baghdadites” who preserved the traditions of the old country. Among the most famous Baghdad families were the Gabai, the Khadhooris and the Sassoons, the latter of which built a flourishing international trade network that stretched from India through Shanghai and Cuba to England.

The Sassoons and Khadoories created huge, competing business empires, helped open China to the West and aided Jewish refugees in Shanghai during the Shoah – They are considered rival Iraqi Jewish Clans that Changed the Face of Shanghai.

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad in India are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Indo-Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Beginning in the 18th century, merchant traders from Baghdad and Aleppo established Jewish communities in India in a trading network across Asia which flourished under the British Empire in the 19th century. By the early 19th century, trade between Baghdad and India was said to be entirely in the hands of the Jewish community. The deteriorating situation in the Ottoman Empire and the rise of commercial opportunities in British India saw many Jews from Iraq establish themselves permanently in India, at first in Surat, then especially in Calcutta and Bombay.

These communities continued to grow creating a tight trading and kinship network across Asia. Smaller Baghdadi communities were established beyond India in the mid-nineteenth century in Burma, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. Baghdadi trading outposts were also established across colonial Asia when families settled in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Australia.

The Second World War brought strife to India and an end to the British Empire in Asia. Dislocated by war, the violence of the Indian Partition, rising nationalism, and the uncertainty of independence, an exodus began to the newly founded state of Israel, Britain, and Australia. Their old trade routes severed first by Communist victory in Asia, the ocean trade stifled in India and Burma by postcolonial nationalizations and trade restrictions.

The Baghdadi Jews

Families of Baghdadi Jewish descent continue to play a major role in Jewish life, especially in Great Britain where families such as the Sassoon’s and Reuben’s enjoyed great prominence in business and politics. The Baghdadi Jews emigrated almost entirely by the 1970s.

Among the wealthy Baghdadi Jews was the famed merchant and landlord Khadhoori Sha’ashooa who had three palaces built along the Tigress river. King Faisal I took one of these places as his first office. Other wealthy Jewish families in the twenties were Khadhoori Lawi, Ffrank Ainy, The Mashaal, the Tweeq, The Shukur, The Mkamal, Someekh, the Dangoor families as well as Ibrahiem Haiem, Edwar Aboudi, philantropoist Me’ir Alias, Aliazer Khadhoori, Massouda Shantoob.

In 1917, following the fall of the Turkish Empire, the British took over the Land of Two Rivers and gave control of it to King Faisal I. The reign of Faisal I is considered the golden age of Iraq's Jews in the 20th century. The Jewish community received representation in the Iraqi parliament, and its trade ties with the British tightened further. The latter gave the Jewish merchants a few import-export lines owned by the British West Indies Corporations, thus allowing them control over a large part of the goods entering Iraq.

During the British Mandate beginning in 1920, and in the early days after independence of Iraq in 1932, well-educated Jews played an important role in civic life. Throughout this period, the authorities drew heavily on the talents of the well-educated Jews for their ties outside the country and proficiency in foreign languages.

Iraq’s first minister of finance, Yehezkel Sassoon, was a Jew. Iraqi Jews played a vital role in the development of judicial and postal systems. Records from the Baghdad Chamber of Commerce show that 10 out of its 19 members in 1947 were Jews and the first musical band formed for Baghdad's nascent radio in the 1930s consisted mainly of Jews. Jews were represented in the Iraqi parliament, and many Jews held significant positions in the bureaucracy.

In the 1936 Iraq Directory, the “Israelite community” is listed among the various other Iraqi communities, such as Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Muslims, Christians, Yazidis and Sabeans, and numbering at about 120,000. Hebrew was also listed as one of Iraq’s six languages.

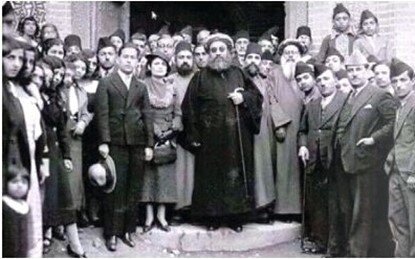

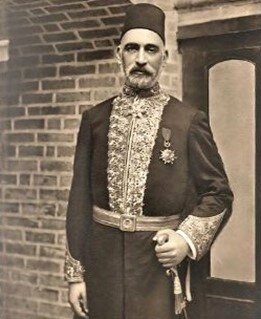

The prominent Jewish trader Hezkell Sassoon, nicknamed “The Rothschild of the East”, was the first Jewish Treasury Minister in Iraq, a leader of the Iraqi national movement, a statesman and financier. Sir Sassoon Heskell, KBE (17 March 1860 – 31 August 1932) also known as Sassoon Effendi (from Turkish Effendi, a title meaning Lord), along with Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence were instrumental in the creation and the establishment of the Kingdom of Iraq post Ottoman rule and founded the nascent Iraqi government’s laws and financial structure.

He was knighted by King George V in 1923. King Faisal I conferred on him the Civil Raffidain Medal Grade II, the Shahinshah awarded him the Shir-o-Khorshi medal, and the Ottoman Empire decorated him with the Al-Moutamayez (excellence) Medal.

During his period as Minister of Finance, Sassoon founded all the financial and budgeting structures and the laws for the Kingdom. He looked whole-heartedly after the interests of the monarchy and the proper fulfilment of its laws. Rather famously, one of his most financially prolific deeds for the State was during negotiations with the British Petroleum Company in 1925. Through a pure stroke of genius and foresight, Sir Sassoon demanded that Iraq’s oil revenue be remunerated in GOLD rather than Sterling. At the time, this request seemed bizarre since sterling was backed by the Gold Standard, nevertheless, his demand was reluctantly accepted. Later this concession benefited Iraq’s treasury during world War II, when the gold standard was abandoned, and sterling plummeted. He thus secured countless additional millions of Iraqi Dinars for the State. This is something that the Iraqi nation remembers with much appreciation and admiration.

He was a far-sighted statesman with a profoundly deep knowledge of Iraq and other countries. Sasoon was immensely well-travelled and well acquainted with most major European statesmen of the time. Sasoon Heskell, was buried in Paris. Sassoon certainly deserves a statue in the heart of old Baghdad.

The world of Jewish education also benefited from the general prosperity. The global school network Alliance Israelite Universally established educational institutions which combined the teaching of Hebrew with modern fields of knowledge and made a crucial contribution to the connection between tradition and secular life among Iraq's Jews.

Prior to the late1940s, many Jewish schools served the Baghdad Jewish community, educating Jewish, Christian, and Muslim students in Arabic, Hebrew, English, and French. The Jewish schools were run under the auspices of the local Jewish communal structure, the Iraqi government, and the international Jewish organizations based in Paris and London. The Frank Inny School was the last Jewish school to remain open in Baghdad, closing in 1973.

Over 60 copies of this Hebrew elementary school primer were found in the Mukhabarat headquarters, the only title to be found with so many duplicates. Almost all the copies are missing pages 73-74, which had a Hebrew text and poem declaring loyalty to King Faisal II. After Faisal was killed in a military coup in July 1958, these texts were removed.

It was this enlightened atmosphere that saw the birth of figures who would one day become the intellectual elite of the Baghdad-descended Jews, among them Professor Shmuel (Sami) Moreh who wrote in Arabic, Hebrew, and English, Samir Nakash, Sami Michael, Prof. Sassoon Somech, Poets Anwar Sha’aool, Murad Mikhael, and distinguished writer Mi’er Basr (Meir Shloumohay Shaoul Basliel), academic Ahmmed Sossa.

Jewish personalities shined in various fields and disciplines in Iraq, in art, literature, journalism, and medicine. In the field of journalism, Jews played an active role, inclusive of Salim Al-Bassoun and Naim Tuwaiq, whom Kamel Al-Chadirji heavily relied on for editing the Al-Ahali newspaper, and journalist Anwar Shaul. The journalist Niran Al-Bassoun stated: “I am the daughter of Iraq, in my body the Tigris and Euphrates flow. Like an artery and vein, and no one can take Iraq away from me, even if they remove me from Iraq. I was forcibly displaced from the heart of Iraq, but no one was able to take Iraq from my heart.”

There was ferocity and an open mindedness to the domination of the Iraqi Jews in the field of printing and publishing, as evidenced by the printing presses that they established during the first half of the twentieth century. These presses were found in about fifteen printing houses, and were utilized to print books, newspapers, and magazines, for various scientific and literary publications, business accessories and other publications.

In medicine: Dr. Jack Abood Shabby, Dr. Munier Suliman, Dr. Albeer Hakim, Dr. Dawood Gabbay, Dr. Gurgy Rabi’eh, Dr. Ihsan Samra.

Philanthropist Manheim Daniel - Basrawi, Sassoon Sousa, Naiem Jala’adi (Khalasachi) from Hilla, journalist Salim Basoon, Niran Basoon and others, who defined themselves as “Arab Jews” and combined the Arab-Muslim culture with the Jewish one in their works.

Iraq has one of the world's oldest cultural histories and boasts a rich heritage. Iraqi Maqam is a type of Arab maqam music found in Iraq that is around four-hundred years old. The collection of instruments used in this kind of music, called Al-Chalghi al-Baghdadi, includes a Qari’ (vocalist), Santur, Jawza, Dunbug/Dumbug, and occasionally, riq/naqqarat.

In Iraqi folklore and recording industry, most notably famed singer Salima Murad Pasha who was married to Iraq’s top singer (Nadhum Al-Ghazali), the brothers composers Dawood and Salih Al-Kuwaiti, Maqam singers Filfil Gurjy, Yousif Horisho.

Nearly all the members of the Baghdad Symphony Orchestra were Jewish. Yet this flourishing environment abruptly ended in 1947, with the partition of Palestine and the fight for Israel’s independence. Outbreaks of anti-Jewish rioting regularly occurred between 1947 and 1949.

The persecution of Jews within Iraq, and especially the support for Nazi Germany voiced by certain Pan-Arab nationalists, pushed Iraqi Jews towards communism. Often, joining the ICP marked an Iraqi, as opposed to an Arab, choice. Being an Iraqi communist meant seeing the Kurds and the Turkmans, the Shi’es, the Sunnis, and the Christians as comrades in a shared struggle. Iraqi-Jewish communists, although loyal to the party’s internationalist, antireligious ideals, joined its ranks because of their Jewish identity. Shimon Ballas’s (b. 1930) joined the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) at the age of 16. In 1951, with the growing persecution of both communists and Jews in Iraq, Ballas immigrated to Israel.

The establishment of the State of Israel and the War of Independence (In which the Iraqi army took part on the Arab side) created a chokehold around the necks of Iraq's Jews, who were seen as a fifth column and as having double loyalties and identities. Iraqi nationalists threw bombs at Jewish institutions and synagogues in Baghdad, and Iraqi law forbade the Jews to leave the country.

Among the stories etched in the memory of the Iraqis about the Jews, and anecdotes that the author Mazen Latif relates about the Jews of Diwaniyah in his article entitled “The Jews of Diwaniyah - Names and Memories,” is when one of the Diwaniyah Jews knocked on the door of his poor Muslim neighbor and told him that all his property would be confiscated by the dictatorial regime that ordered his displacement and asked him to willingly take from him his most asset.” The man slapped his head and said, “If I lose you as my neighbor what good is money!”, preferring noble poverty over wealth with villainy.

With very few exceptions, only Jews wore watches. On spotting one that looked expensive, a policeman had approached the owner as if to ask the hour. Once assured the man was Jewish, he relieved him of the timepiece and took him into custody. The watch, he told the judge, contained a tiny wireless; he had caught the Jew, he claimed, sending military secrets to the Zionists in Palestine. Without examining the "evidence" or asking any questions, the judge pronounced his sentence. The "traitor" went to prison, the watch to the policeman as reward."

The unraveling of Jewish life in Iraq began in the mid part of the 20th century, accelerating after the advent of Nazism to power in Germany and the proliferation of anti-Jewish propaganda. In June 1941, in the aftermath of the defeat of the pro-Nazi Iraqi regime, an anti-Jewish attack broke out in Baghdad during the Jewish festival of Shavuot. The unprecedented attack, known as the Farhud ("violent dispossession”) shattered the sense of safety and security of the Jews. The numbers speak loudly, in (1948 | 150,000 - 2014 | 60 Jews -2018 |10 - 2020 | Zero).

Before the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, Iraq's prime minister Nuri Al-Saied told British diplomats that if the United Nations solution were not "satisfactory", "severe measures would be taken against all Jews in Arab countries". In a speech at the General Assembly Hall at Flushing Meadow, New York, on Friday, 28 November 1947, Iraq's Foreign Minister, Fadel Jamalli, included the following statement:

“Partition imposed against the will of most of the people will jeopardize peace and harmony in the Middle East. Not only the uprising of the Arabs of Palestine is to be expected, but the masses in the Arab world cannot be restrained. The Arab-Jewish relationship in the Arab world will greatly deteriorate. There are more Jews in the Arab world outside of Palestine than there are in Palestine. In Iraq alone, we have about one hundred and fifty thousand Jews who share with Moslems and Christians all the advantages of political and economic rights. Harmony prevails among Moslems, Christians, and Jews. But any injustice imposed upon the Arabs of Palestine will disturb the harmony among Jews and non-Jews in Iraq; it will breed inter-religious prejudice and hatred.”

In the next issue we will continue the Iraqi Jewish community story of Farhud and the Exodus.