The Bishop of Union

Mar Bawai Soro’s journey home to the Catholic Church

By Crystal Kassab Jabiro

There have long been stories—almost mythological in nature—about the Assyrian Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church uniting as one. A romanticized vision of ecclesial reunion, born centuries ago in Mesopotamia, found its way to America in the 1970s. For some, that vision eventually became a shattered dream—a bubble burst after years of hopeful anticipation.

At the center of this narrative was Mar (Bishop) Bawai Soro, an Assyrian Church of the East bishop who was later received into the Catholic Church. He is also the co-author of The Chaldean Catholic Church, part of Arcadia Publishing’s “Images of America” series.

His Excellency was born in 1954 in Kirkuk, Iraq, but was raised in Baghdad’s predominantly Chaldean neighborhood of Kharbanda. Although his family belonged to the Assyrian Church of the East, he attended St. Joseph Chaldean Catholic School. He later attended Sharkia High School, a public institution, where he excelled in English and mathematics. It was during that period that he underwent a major personal transformation, largely due to ordinary yet profound conversations with his father.

“My dad would talk to me about life and faith, and he really kindled in my heart a keen interest in the priesthood,” said Bishop Soro, now 71. “Both my parents and all my grandparents were extremely decent people and deeply religious. That’s what made me fall in love with God.”

The 15 years of political upheaval in Iraq from 1958 to 1973 led the Soro family to believe the country would no longer be hospitable to Christians.

“It has been the Christians’ story to survive in our homeland for fourteen centuries,” said Bishop Soro. “We buy our comfort when we shut our mouths.”

Ultimately, silence gave way to exile. In 1973, he traveled to Lebanon while awaiting a visa to Australia. But in 1974, the Lebanese Civil War broke out. Two years later, Bishop Soro was accepted as a refugee to the United States. He arrived in Chicago, Illinois, sponsored by relatives. There, he enrolled at Truman College, a community college in the city, and studied humanities for two years—a decision that deepened his vocational calling.

“I wanted to pursue knowledge and personal growth,” he reflected. “The more I matured, the more my self-understanding developed. I realized that my happiness in life would only be fulfilled through loving and serving God above all else.”

LISTEN TO THIS STORY!

CN Audio Stories are made possible with generous support from the Chaldean American Chamber of Commerce

He was mentored by Assyrian priests in Chicago, who taught him classical Aramaic and liturgical practices, as the Assyrian Church of the East—often historically referred to as the “Nestorian” Church—lacked formal seminary training for its clergy.

In 1982, he became the first Assyrian priest in Canada, ministering primarily in Toronto but also serving communities in Montreal, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver. Two years later, at age 30, he was elected bishop by the Assyrian Holy Synod and assigned to San Jose, California, where he served at Mar Yosip Assyrian Cathedral for more than two decades.

According to Bishop Soro, it was in the early 1980s that the late Assyrian Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV recognized the importance of ending the Assyrian Church’s isolation from other Christian traditions. Since its early existence outside the Roman Empire, the Church of the East had never been officially aligned with Catholicism, Orthodoxy or Protestantism. Yet the patriarch had the vision and discernment to move the Church closer to the other apostolic traditions.

Bishop Soro, who shared this ecumenical vision, was asked by the Synod to become the catalyst for dialogue and cooperation.

The Catholic Church was the first to respond.

The Vatican offered Bishop Soro two academic scholarships. The first, from 1987 to 1991, allowed him to study at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., where he earned an accelerated undergraduate degree in theology and a Master of Arts in ecclesiology. The second, from 1996 to 2000, enabled him to pursue advanced studies at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome, where he earned a licentiate and doctorate in ecclesiology.

Throughout his academic pursuits, Bishop Soro continued to administer his diocese, participate in international conferences, and represent the Assyrian Church in key theological dialogues—with the Catholic Church, the Coptic Orthodox Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church.

He frequently traveled to Assyrian dioceses in the Middle East, the United States and Australia to offer educational seminars, keeping clergy and laity informed about the progress of ecumenical efforts.

“The Assyrians were carefully monitoring all parts of this ecumenical journey, and their feelings were often a ‘mixed bag,’” the bishop said.

The Assyrian Church of the East took pride in him as the first Assyrian bishop to earn academic degrees and to lead widespread dialogue and consultations.

As his theological understanding deepened, Bishop Soro reached a decisive conclusion: “All the Apostolic Churches legitimately stem from our Lord, but the Catholic Church is the fullest manifestation of the one Church which Christ established on earth.”

He added, “Predictably, of all the dialogues that the Assyrian Church held during these years, the Catholic-Assyrian was the most serious, significant and promising. According to Vatican insiders, this dialogue was viewed as the most hopeful.”

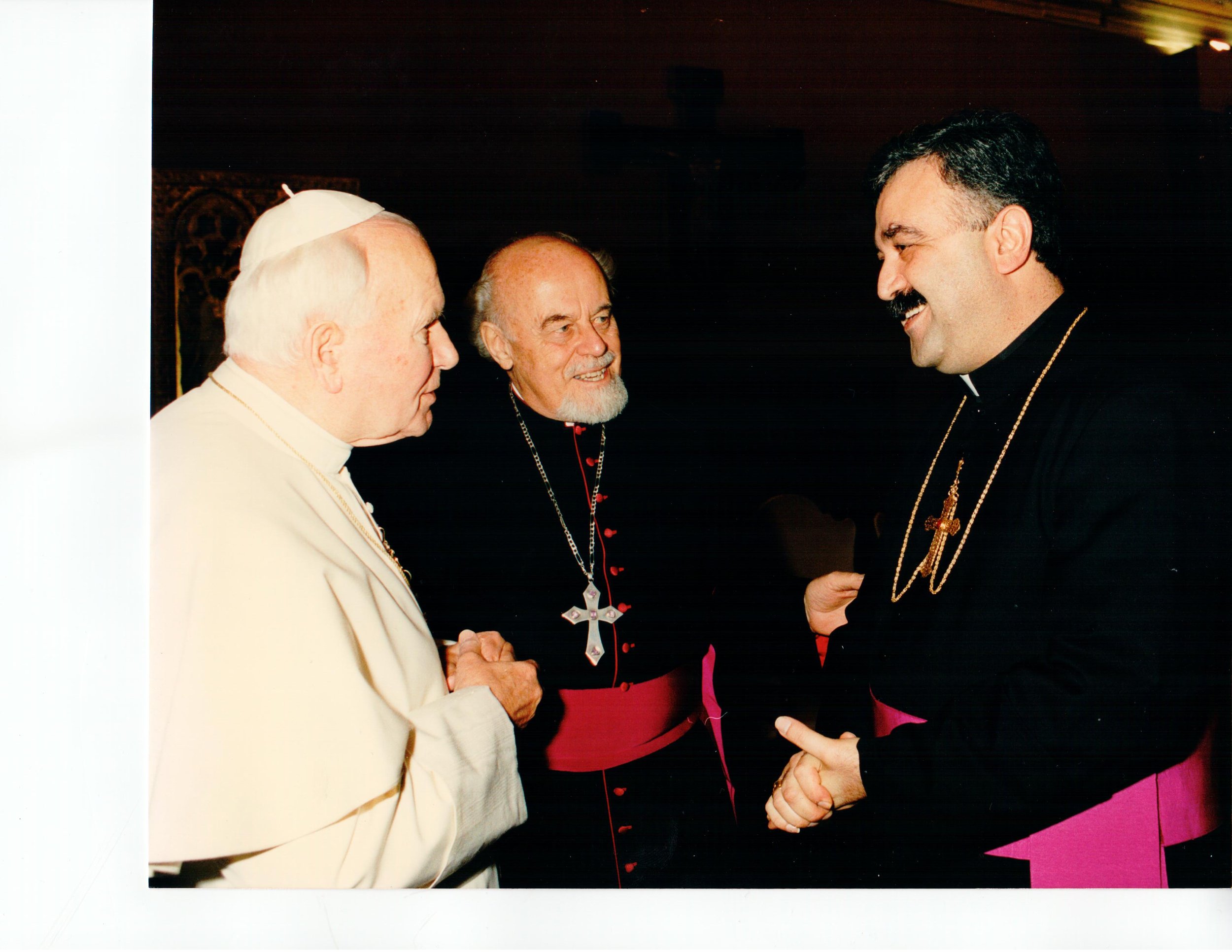

In 1994, Saint Pope John Paul II

and Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV signed

the Common Christological Decla-ration, affirming their shared faith in Christ and addressing long-standing theological misunderstandings, inclu-ding accusations of “Nestorianism.” This milestone opened the door to the possibility of full ecclesial communion.

It also sparked an internal dialogue between Assyrians and Chaldeans.

Had the Assyrian Church of the East entered into communion with Rome, it could have paved the way for full unity with the Chaldean Catholic Church. By the dawn of the third millennium, 1.5 million Iraqi Christians might have become one body—strengthening Christian witness in a post-Saddam Iraq.

Unfortunately, the path proved more complicated.

During multiple synodal encounters in Chicago, Beirut and Baghdad, the two churches raised distinct concerns.

The Assyrian Church of the East insisted that, following unification:

The Chaldean Church should no longer adhere to papal primacy but instead submit to the authority of a patriarch elected by the united synod of both churches.

All faithful of the united church should adopt “Assyrian” as their national identity.

The Chaldean Church, in contrast, proposed:

Recognition of papal primacy as a condition for unity.

Continued use of the term “Chaldean” for those who preferred it, with a combined name for the united church possibly being “Chaldo-Assyrian” or “Assyro-Chaldean.”

Liturgical reforms to bring the faithful closer to the spirit and meaning of divine worship and sacramental life.

“Sadly, at this point,” said Bishop Soro, “basic agreement between the Assyrians and the Chaldeans seemed like a proposition very far in the future.”

Historical and sociological tensions played a vital role. For centuries, the Assyrian Church’s ecclesiology emphasized its independence from Rome. Any talk of communion was seen by many Assyrians as a loss of identity. Meanwhile, the Chaldean Church had been in communion with Rome since the 16th century.

Bishop Soro explained why the term “Chaldean” became associated with the Catholic branch of the Church of the East. “Because Mar Youhanan Sulaqa, from the region of Nineveh, was appointed patriarch by Pope Julius III in 1553, his title was ‘Patriarch of Mosul and Athur (Assyria).’ Rome could not designate his Catholic branch of the Church of the East as ‘Nestorian Catholic’ because the term ‘Nestorian’ carried heretical connotations.”

By 1565, Rome officially began designating the Catholic branch as “Chaldean,” based on three historical considerations:

“Chaldean” was the name of the last native empire in Mesopotamia (626–539 BCE) before foreign powers such as the Parthians, Muslim Arabs, Mongols and Ottoman Turks ruled the region for 2,500 years.

The name carried biblical prestige, as Abraham was said to be from “Ur of the Chaldees.”

The Gospel of Matthew mentions the Magi who, led by a star, came from the East—most likely Babylon—to Bethlehem to worship the newborn King of the Jews, Jesus, and offer him gifts.

By the Jubilee Year of 2000, differences between the Assyrian and Chaldean churches remained unresolved—largely due to disagreements over papal primacy and nomenclature. Bishop Soro’s continued advocacy for full communion with Rome and unity with the Chaldeans eventually led the Assyrian Church of the East to reject his views and actions. In 2005, he was condemned, suspended and laicized by the Assyrian hierarchy. While many saw his stance as a betrayal, he retained a loyal following.

Bishop Soro, along with six priests and more than 1,000 families, continued their journey home to the Catholic Church. By 2009, he had moved to San Diego, where he was welcomed by the late Bishop Sarhad Jammo and Bishop Ibrahim N. Ibrahim of Michigan.

“Bishops Jammo and Ibrahim were open-minded and open-hearted,” Bishop Soro said. “They canonically received all my followers into the Chaldean Church and helped me continue serving them in California and Chicago.”

In 2014, Pope Francis formally appointed Bishop Soro to serve in San Diego. Three years later, the pope named him the third bishop of the Chaldean Eparchy of Canada. Bishop Soro served in Toronto until his retirement in late 2021—completing a full-circle journey that began with his first priestly assignment nearly 40 years earlier. He then returned to San Diego, where he recently co-authored a book on the Chaldean Church with his close friend Jacob Bacall.

“Ultimately, my experience in life taught me that, in order to be a good Christian, one must never make Christianity about themselves,” Bishop Soro said. “It must always be about God and His providence in our lives. If we do this, we become icons reflecting the image of Christ to the world.”