Origins of the Written Word: Cuneiform

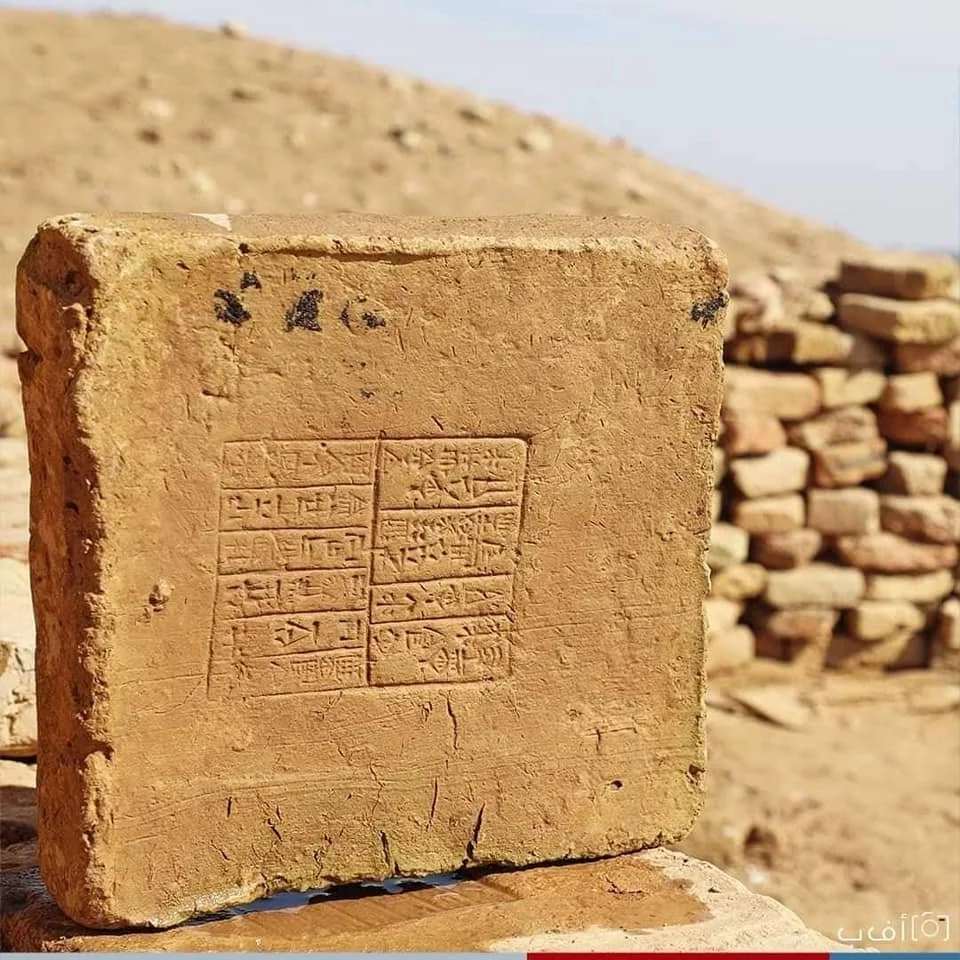

A mud brick bearing a cuneiform inscription is seen during excavation at the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu, now known as Tello, in Iraq’s al-Shatrah district of the southern Dhi Qar province on November 14, 2021.

By Adhid Miri, PhD

Mesopotamia, located in what is now Iraq, is considered the birthplace of writing and with it, recorded history. Its people also built the world’s first cities and developed the oldest known political and administrative systems and drafted the first known letter. The very idea of philosophy was introduced in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The earliest known writing was invented there around 3,400 B.C. in an area called Sumer near the Persian Gulf. The development of Sumerian script was influenced by local materials, clay for tablets and reeds for styluses. At about the same time, or a little later, the Egyptians were inventing their own form of hieroglyphic writing.

Writing (visible signs of ideas, words, and symbols) emerged in many different cultures in the Bronze Age. Archaeological discoveries in ancient Mesopotamia show the initial power and purpose of writing, from administrative and legal functions to poetry and literature. Scholars generally agree that the earliest form of writing appeared almost 5,500 years ago in ancient Sumer and spread over the world from there via a process of cultural diffusion.

Even after Sumerian died out as a spoken language around 2,000 B.C., it survived as a scholarly language and script. Other people within and near Mesopotamia—from Turkey, Syria, and from Egypt to Iran—adopted the later version of this script developed by the Akkadians (the first recognizable Semitic people), who succeeded the Sumerians as rulers of Mesopotamia. In Babylonia itself, the script survived for two more millennia until its demise around 70 C.E.

Before the Written Word

For thousands of years, long before the invention of the true written word, people used symbols to keep essential records. The earliest form of notetaking known in the Middle East, the “tally bone,” dates back 30,000 years. The bones recorded lunar months, which governed the ritual cycles observed by hunter gatherers.

From 9000-3000 BC, people in the Middle East used clay tokens to record commercial transactions, sealing them into clay envelopes called bullae. A token’s shape symbolized either goods (animals, grain, trees) or specific large numbers. At around the same time, the seal, (a detail-engraved image identifying the sender of the message) was developed. The seal was pressed on wet clay by stamping, or in the case of cylinder seals, by rolling.

Every human community possesses language, a feature regarded as a defining condition of mankind. However, the development of writing systems, and their partial supplantation of traditional oral systems of communication, have been sporadic, uneven, and slow. Once established, writing systems on the whole change more slowly than their spoken counterparts, and often preserve features and expressions which are no longer current in the spoken language. A great benefit of writing is that it provides a persistent record of information expressed in a language, which can be retrieved at a future date.

Cuneiform

Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system invented around 3400 B.C. Scribes used symbols built from wedge-shaped impressions pressed into clay or carved into stone. Many languages and civilizations used cuneiform, from Sumerian to Persian. The rise, fall, and rediscovery of cuneiform tells the story of the written word.

The invention of writing is considered the most important event in the intellectual history of humankind. It separates the prehistoric stage from subsequent historical stages. In this context, we must point out that while we believe cuneiform writing to be the oldest writing in the history of mankind, history must include Egyptian writing, which the Greek called hieroglyphics. It appeared in the same period but unlike the Sumerian writing, hieroglyphics depicted pictures rather than letters.

The emergence of writing in each area is usually followed by several centuries of fragmentary inscriptions. Historians mark the “historicity” of a culture by the presence of coherent texts in the culture’s writing system(s).

The four Mesopotamian civilizations—Sumer, Babylon, Akkad, and Assyria—were centers of science and knowledge. The Sumerian cuneiform script was adapted for the writing of the Akkadian, Elamite, Hittite (and Luwian), Hurrian (and Urartian) languages, and it inspired the old Persian and Ugaritic national alphabets. Although it then disappeared when these cultures faded and new scripts (such as the Phoenician alphabet) developed, numerous clay tablets and stelae (such as those upon which the Code of Hammurabi is written) remained in use.

While the cuneiform writing system was created and used at first only by the Sumerians, it did not take long before neighboring groups adopted it for their own use. By about 2500 BC, the Akkadians, a Semitic-speaking people that dwelled north of the Sumerians, starting using cuneiform to write their own language. However, it was the ascendency of the Akkadian dynasty in 2300 BC that positioned Akkadian over Sumerian as the primary language of Mesopotamia.

While Sumerian did enjoy a quick revival, it eventually became a dead language used only in literary contexts, whereas Akkadian would continue to be spoken for the next two millennium and evolved into later (more famous) forms known as Babylonian and Assyrian.

Writing Tools

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train as scribes, in the service of temple, pharisaic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was difficult to learn, but in later centuries may have been intentionally made even more difficult, as this preserved the scribes’ position.

The development of the Sumerian script was influenced by local materials: clay for tablets and reeds for styluses (writing tools). They wrote on clay, on stone, on silver, on gold on papyrus and on deerskin, in cuneiform and with the alphabet in Akkadian and Aramaic. They never stopped writing. In times of peace and in times of war. Through famine and in times of tribulation. No other ancient civilization has bequeathed to the world so vast a corpus of documents. There are about 130,000 mud slabs of Mesopotamia in the British Museum.

Cuneiform writing continued for a few centuries BC and was adapted to write in at least fifteen different languages. The last dated cuneiform text has a date corresponding to A.D. 75, although the script probably continued in use over the next two centuries and was replaced by the Levant alphabetic writing that began to spread with the spread of the Aramaic language, especially during the reign of the last (South Chaldean) dynasty.

The original Sumerian writing system derives from a system of clay tokens used to represent commodities. By the end of the 4th millennium BC, this had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a round-shaped stylus impressed into soft clay at different angles for recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with pictographic writing using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted.

Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing were gradually replaced around 2700-2500 BC by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms, but developed to include phonetic elements by the 29th century BC. About 2600 BC cuneiform began to represent syllables of the Sumerian language.

Finally, cuneiform writing became a general-purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers. From the 26th century BC, this script was adapted to the Akkadian language, and from there to others such as Hurrian and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian.

Nabu

In the time of Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 BC), the God Nabu (a divine patron of scribes) received the Sumerian Goddess Nisaba’s attributes and became the patron of writing and scribes. Nisaba was still venerated and didn’t disappear from the pantheon, but from that moment on, she was known as Nabu’s wife. Nabu was very important for the Babylonians and was adopted by the Assyrians as the son of their supreme god, Ashur.

In the 1800s and 1900s, archaeological excavations revealed thousands of cuneiform documents, and the variations of the script across languages and time were slowly deciphered.

While we can read cuneiform documents today, the majority—many hundreds of thousands—still survive unread, and the few hundred cuneiform experts worldwide face an impossible task. Fortunately, machine learning and artificial intelligence offers potential assistance. Scholars at many institutions are compiling databases and training machines to read and fill in gaps in these ancient texts.

Calligraphy

Arabic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting Arabic script in a fluid manner to convey harmony, grace, and beauty. It was primarily developed as a way of delivering the Word of God through the holy scripture of the Qur’an and is considered the quintessential art form of the Islamic world. Arabic letters decorate objects ranging from mosques to palaces, carpets, and paintings.

The practice, which can be passed down through formal and informal education, uses the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet, written in cursive, from right to left. Originally intended to make writing clear and legible, it gradually became an Islamic Arab art for traditional and modern works.

Arabic consists of 17 characters, which, with the addition of dots placed above or below certain of them, provide the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet. Arabic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting based on the Arabic alphabet. It is known in Arabic as Khatt and the calligrapher as Khattat. Calligraphers are highly regarded in the Islamic culture.

The art of calligraphy has universal appeal, and that is why it developed so quickly and became so sought-after from the Middle Ages onwards. Its beautiful proportions and exquisite luminosity are something that everyone can appreciate.

An Arabic calligrapher employs a reed pen, called a Qalam, with the working point cut on an angle. This feature produces a thick downstroke and a thin upstroke with an infinity of gradation in between. The nice balance between the vertical above and the open curve below the middle register induces a sense of harmony. The peculiarity that certain letters cannot be joined to their neighbors provides articulation. The line traced by a skilled calligrapher is a true marvel of fluidity and sensitive inflection, communicating the very action of the master’s hand.

In the early centuries of Islam, Arabic not only was the official language of administration but also was and has remained the language of religion and learning. The Arabic alphabet has been adapted to the Islamic peoples’ vernaculars just as the Latin alphabet has been in the Christian-influenced West.

The evolution of writing is a collection of significant events in the alphabet’s history accented by the civilizations, cultures and people who made it happen and correlated with world affairs. Our Chaldean News stories seek to breathe life into what is considered by many to be antiquated and old subjects; however, our themes constantly change, and we remain steadfast in our commitment to revisit history and revive our culture with articles, insight, and words.

Sources: Iraqi Museum, Encyclopedia Britanica, Musée du Louvre, Sjur Cappelen Papazian, Shelby Brown, Christie’s Online, Andre Parrot (The Arts of Assyria).