Habib Hannona – Man of many talents

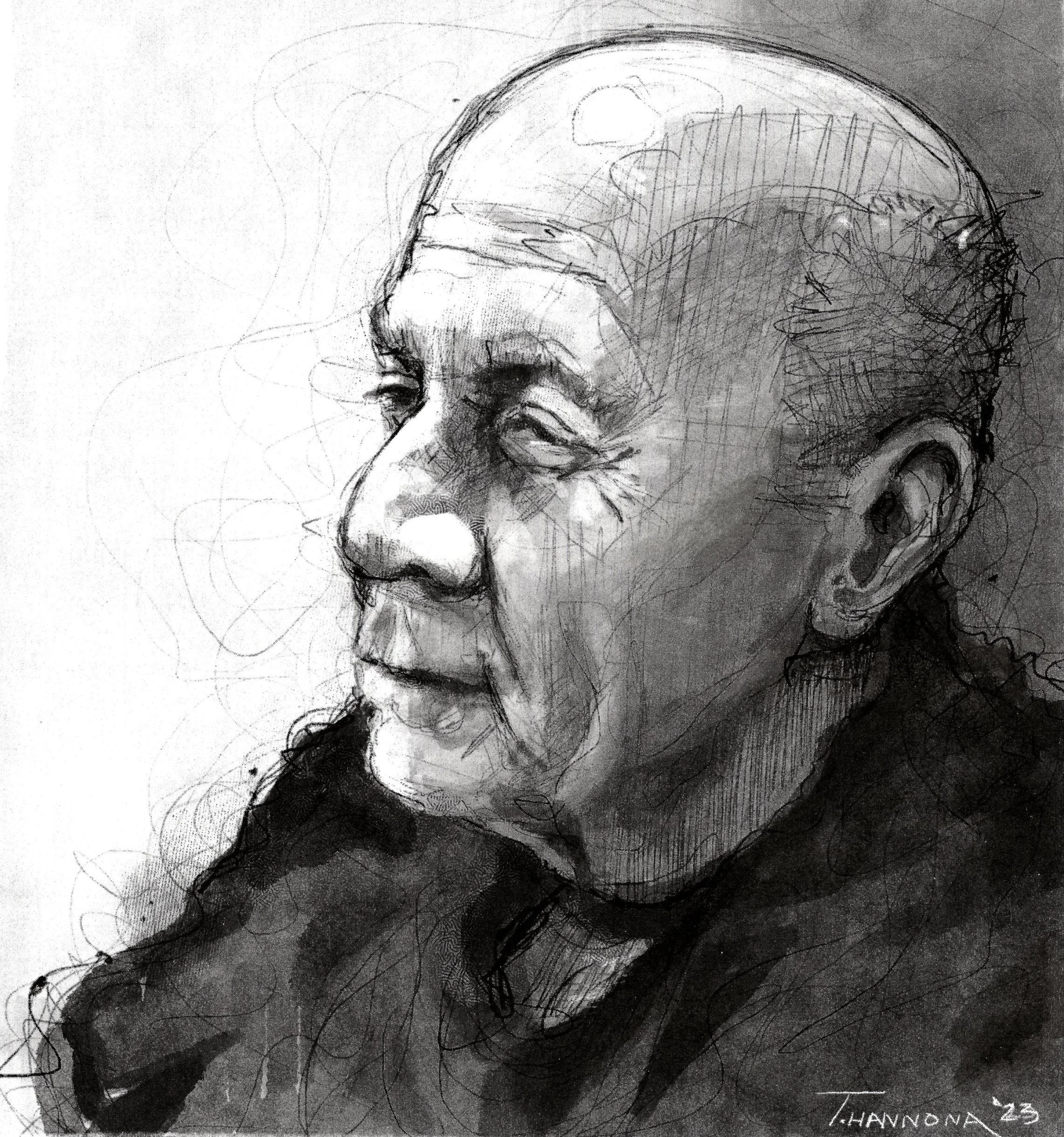

Sketch of Habib Hannona by his son Thamir Hannona

By Adhid Miri, PhD

Part II

It has been said that what shapes a person is the books they’ve read, the people they’ve met, and the places they’ve traveled. This applies directly to Habib Hannona’s life journey and philosophy. As an avid reader and ardent culturist, he has read hundreds, perhaps thousands of books in various languages over the years. This civilized (and civilizing) person does not claim to comprehend them all, but they have certainly contributed to the man that Habib is today.

Over a span of many decades, he assembled a large library, donating part of it to the Babylon College of Iraq. The donation included twenty-two manuscripts written in Eastern Aramaic script, some dating back three hundred years or more. Other books were donated to Mar Addy Library in Karemlash.

“If you know or learn something good, do not keep it for yourself, but present it and share it with others, so that they may enjoy like you,” says Habib. “For this, I worked with patience, deliberation, and humility to enrich the library with products.

“I also have other projects that I hope will see the light of day.”

The School of Time

Habib considers himself a writer and researcher on the history of Mesopotamia and has published many related books and manuscripts and dozens of historical articles in magazines such as Sawt Al-Ummah, Al-Kalima, Venus, The Forum, Chaldean Detroit Times, and more. He is also a contributing writer for websites such as Ankawa, Karemlash.net, Baqofa, Ain Noni, and Wikipedia; he stays up to date on current happenings as well.

As an author, Habib believes that geography and history are intertwined. On the sheets and surfaces of geography, history is written. “We are all students of life and the school of time,” he says.

His research over the past 30 years was not limited to the history of Habib’s hometown of Karemlash but also included the history of other Nineveh Plain towns like TelKaif, Alqosh, Baqofa, Batnaya, Bartella, Baghdida, Bashiqa, Bahzani, and others.

“My love for history prompted me to research the language as well,” says Habib. “I studied the cuneiform-Akkadian language and its vocabulary inherited in the ‘Language of Swarth.’” He found the subject so interesting that he wrote a book about it called Alsworth and Akkadian.

Habib’s research took about ten years, from 1977 to 1987. When complete, he presented it to Dr. Yousif Habbi, the Dean of Babylon College, for his review and opinion. “After reviewing it,” Habib remembers, “he liked it so much he suggested that I expand the material and submit it to an academic body, such as the Iraqi College of Arts, as an academic thesis to obtain a Master’s or a PhD degree.”

But life happened. The deteriorating conditions in Iraq strongly affected Habib so he decided to emigrate. “Dr. Habbi deeply regretted my decision when he learned of my desire to emigrate,” says Habib, “and the failure to achieve his proposal to submit my work to the college faculty.”

The Great Identity Debate

Assyrians and Chaldeans have, for a long time, been intertwined through name and identity.

Hannona challenges the theory that the Chaldean name is a sectarian label, as claimed and perpetuated by many Assyrian zealots. Assyrians claim that the Chaldeans have long since disappeared and no trace of them remains. They additionally assert their current name, Chaldean, is given for a doctrinal designation while in fact they are pure Assyrians.

This fallacy was reputed in Hannona’s authoritative book, Chaldeans and the National Question, published in 2004. In a follow-up lecture on the subject at the Chaldean Cultural Salon in Windsor, Ontario, on December 10, 2016, Hannona provided facts and evidence to settle the ongoing arguments about the Chaldean name and identity.

He first posed the following question: “Can the Chaldeans be considered a people with a national identity like the rest of the nations that appeared on the stage of history?”

Hannona answered his own question by citing the essential components of Chaldean nationalism: A homeland, which is Chaldea in the south of Babylon on the banks of the Arabian or Persian Gulf, whose historical name was the Chaldean Gulf; a common history; common language; a biological bond of blood and genealogy; sociological association such as customs and traditions; social norms and mythology; and common religious beliefs.

The name Chaldo or Chaldea and its holders are ancient historical peoples originating from southern Iraq. Therefore, national designation and not sectarian existed even in those ancient times.

Hannona provided an overview of the history and civilization of the Chaldeans and confirmed that the Chaldeans are one of the oldest peoples in the region. They were mentioned by name in the Old Testament book several times, which confirms their presence deep in the history of Iraq.

Habib points out, “Even though we cannot put a time limit on their appearance in the south between the two rivers, where there were many Chaldean kingdoms, including the powerful kingdom, Beth Yaqin; one of its leaders, Nabobulassar was able to control Babylon in 626 BC. AD, founding the modern Chaldean state.

“The Chaldeans were also among the oldest and most famous pioneers of human civilization, offering astronomy, irrigation, the sexagesimal system, and mathematics,” Habib goes on to say, “which made them famous peoples throughout ancient history.”

Chaldeans spoke the Akkadian language and used cuneiform script in their writing in the days when their kingdoms and state existed. This continued until the advent of Christianity, when the Aramaic language began to take an amazing role in the lives of all of the people of Mesopotamia and beyond. The Chaldeans adopted the Aramaic language after the fall of their state in 539 BC at the hands of the Persians and their leader Cyrus.

The Final Word

Habib is a frequent communicator with many through the website karmelash.net, which he has managed since its establishment in 2010.

“Preserving our culture is not just important,” says Hannona, “but vital for our survival.”

Books were the window through which those interested in the history and heritage of Mesopotamia looked closely at Iraqi Chaldean towns with their rich culture. Karemlash had a distinguished presence on the pages of history books, archeology magazines, and academic forums.

Habib Hannona hopes that this dark night that has befallen his homeland will be cleared, and that Iraq’s unfortunate people will be blessed with security, happiness, and progress, like all peoples who yearn for stability and prosperity; that the rule of law should prevail in the place of jurisprudence, whatever it is, and that the citizen should be treated and measured by their Iraqi origins and patriotism and not by any other measure.

“As immigrants, we are carriers of will and knowledge,” says Hannona, “instruments of building and success, and promoters of vision and hope. We aspire to see a new Iraq that is free, diverse, stable, and prosperous. We hope to see a historic day that will mark a new and deserved future for the good and innocent people of Iraq, a day that will spark opportunity and partnership between the proud people of Iraq and the good people of United States of America.”

Habib yet has hopes for a happy ending, saying “Iraq’s future is a light we cannot see!”

Acknowledgement of material from Habib Hannona and Taghreed Thomas. Excerpts from an article and interview by Kamal Yaldo, Wikipedia. Special editing by Jacqueline Raxter.