Erbil Citadel

A journey through a history of over 6,000 years

By Dr. Adhid Miri

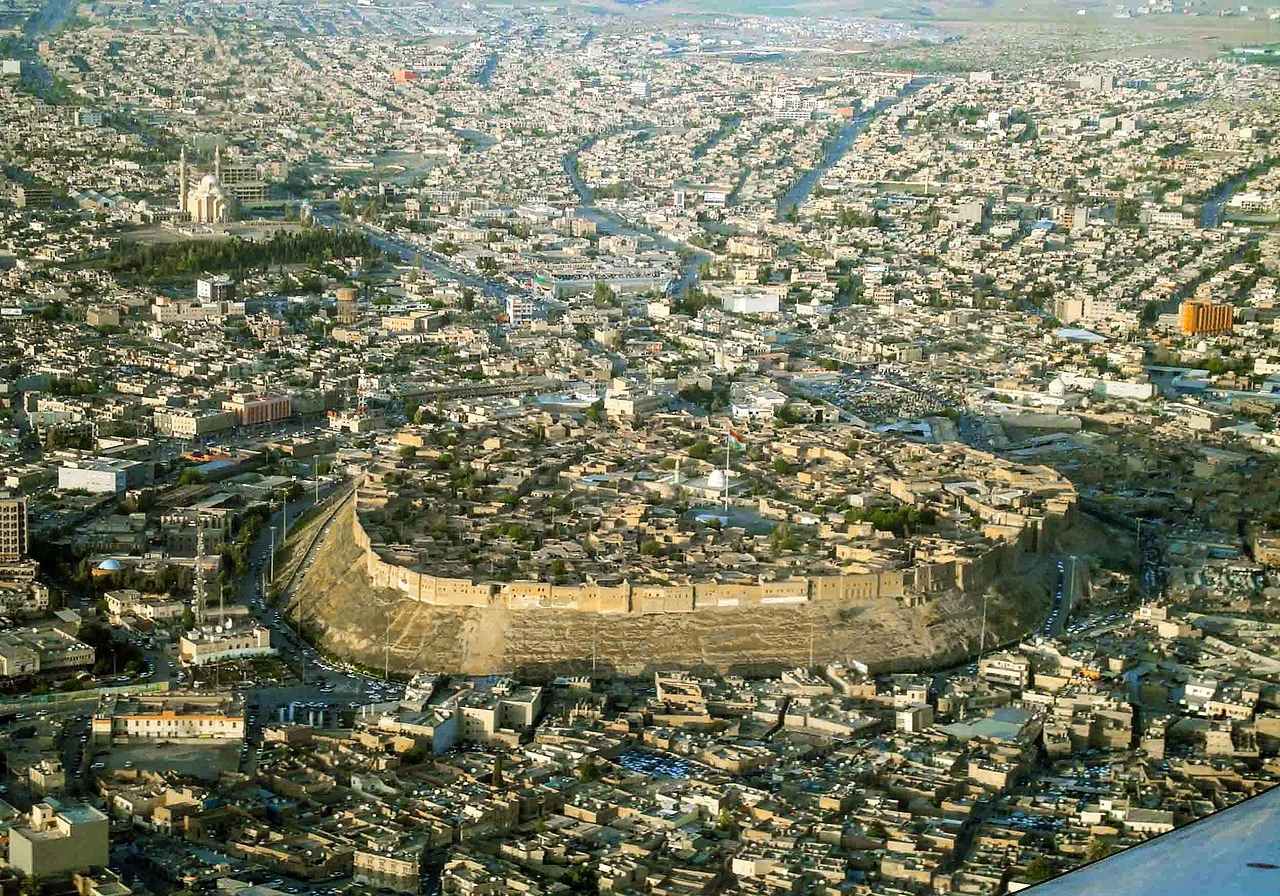

The city of Erbil in northern Iraq is truly magnificent in many ways. Few places on Earth can claim as much uninterrupted history. Erbil is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, with settlement origins dating back at least 8,000 years. Historians assert that the city has been permanently inhabited since the 5th millennium B.C., making it one of humanity’s most ancient urban centers.

Erbil is widely identified with ancient Arbela, a significant Assyrian political and religious hub. The city has been referenced since pre-Sumerian times in numerous written sources, and its name has endured through the millennia: Irbilum, Urbilum, Urbel, Arbail, Arbira, Arbela, and today, Erbil or Arbil. Both written and visual historical records attest to the deep antiquity of settlement at the site.

This region gave rise to some of the most foundational developments in human history—such as the advent of farming and the invention of writing. As a result, the tell (mound) upon which Erbil stands may contain invaluable clues about our shared human past—secrets still buried, waiting to be unearthed.

At the heart of this modern, fast-growing city stands the ancient Erbil Citadel, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is recognized as a rare example of a multilayered archaeological mound that continues to tower over the evolving cityscape that surrounds it. Only by acknowledging the Citadel’s vast age and the many civilizations that once called it home can we begin to appreciate the archaeological wealth hidden beneath its surface.

Over thousands of years, the Citadel has been home to the Sumerians, Akkadians, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Achaemenids, Parthians, Greeks, Romans, Sassanids, Muslims, Timurids, Mongols, Ottomans—and today, the Kurds. It has witnessed endless cycles of habitation, conquest, destruction, and renewal. A true multi-layered archaeological marvel—like a cultural layer cake—its full richness remains tantalizingly just out of reach for the world’s most curious minds.

Ancient History

Erbil was first mentioned in cuneiform texts during the reign of the Sumerian King Shulgi around 2000 B.C. The Babylonians and Assyrians referred to it as Arba Elu, meaning “Four Gods.” Remarkably, Erbil is the only city in the region to have remained continuously inhabited while retaining variations of its original name through the centuries.

Over millennia, Erbil came under the rule of several powerful empires, including the Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes, Achaemenids, and later the Sassanid Persians, Greeks, Parthians, Arabs, and Ottomans. By the time Alexander the Great famously defeated Persian King Darius III at the Battle of Gaugamela—fought about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of the city in 331 B.C.—Erbil was already considered an ancient metropolis. The battle is also known as the Battle of Arbela, after Erbil’s classical name.

The city’s significance and size continued to grow over time. Arbela appears in some of the earliest cuneiform sources, including texts from Ebla in western Syria dated to around 2300 B.C. During the Neo-Assyrian period, the city became a key commercial center and religious hub, home to a major temple complex dedicated to the goddess Ishtar of Arbela.

From the 21st century B.C. until the late 7th century B.C., Erbil was an integral part of the Assyrian Empire. It was later captured by the Gutians yet retained its status as a vital city. During the Neo-Assyrian era, its name was recorded as Arbi-Elu—again meaning “Four Gods”—as well as Urbilim, Arbela, and Arba-Elu in various sources.

Following the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Erbil came under the control of the Medes before being absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire. After Alexander’s victory at Gaugamela, the city became part of his expanding empire.

In the aftermath of Alexander’s death, his generals—the Diadochi—divided the empire, and Erbil, referred to as Arabella or Arbela, became part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Kingdom. By the first century B.C., the city lay at the crossroads of empires once again, contested between the Romans and the Parthians, and known during this period as Arbira.

City of the Four Gods

Erbil, historically known as Arba-Elu—”City of the Four Gods”—was a major religious center in the ancient Near East, rivaling cities like Babylon and Assur. Its patron deity, Ishtar of Erbil, was one of the principal goddesses of Assyria and was frequently mentioned alongside Ishtar of Nineveh. Her sanctuary in Erbil was restored by several Assyrian kings, including Shalmaneser I, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal. Inscriptions from Ashurbanipal recount oracular dreams attributed to the goddess. The king likely held court in Erbil during part of his reign and received envoys there, including a delegation from Rusa II of Urartu following the defeat of the Elamite king Teumman.

By the first century A.D., Arbela (Arba-Elu) had become a significant Christian center. The city was among the earliest to embrace Christianity, and its legacy endures today, with large Christian communities still residing in Erbil and surrounding districts like Ankawa.

Under the Sassanid Empire, Erbil served as the seat of a satrap, or provincial governor. In 340 A.D., Christians in the city faced persecution, and in 358, the governor himself was martyred after converting to Christianity. Around 521, the School of Nisibis established a Nestorian educational institution in Erbil. During this period, the city also hosted a Zoroastrian fire temple, reflecting its religious diversity. Erbil remained an important Christian hub until the ninth century, when the bishopric relocated to Mosul.

Although Muslim forces conquered Erbil in the seventh century, the city retained its religious and cultural diversity for centuries. It wasn’t until the late 14th century, when the Turkic conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) razed the city, that Islam became dominant. By the 1200s, Erbil had already been eclipsed economically by Mosul, about 50 miles to the west, though it continued to serve as a key regional center.

The Mongols launched their first assault on Erbil in 1237, sacking the lower town but failing to seize the citadel due to the approach of a caliphal army. Following the fall of Baghdad in 1258, Hülegü Khan returned to Erbil and captured the citadel after a six-month siege. He appointed a Christian governor, prompting an influx of Jacobite Christians who were permitted to build a church.

However, tolerance gave way to persecution. In 1295, under the Oirat amir Nauruz, systematic attacks on Christians, Jews, and Buddhists began across the Ilkhanate. During the reign of Ilkhan Öljeitü, some Christians in Erbil took refuge in the citadel to escape renewed persecution. In spring 1310, the regional governor (Malek), aided by Kurdish forces, laid siege to the citadel. Despite the efforts of Mar Yahballaha to prevent bloodshed, the fortress fell on July 1, 1310. All the defenders were massacred, along with the Christian population of the lower town.

Ancient Wonder

The Citadel of Erbil is a classic fortified settlement perched atop an egg-shaped mound known as a tell—a steep, man-made hill created over thousands of years by successive layers of human habitation. In archaeology, a tell forms when communities continually rebuild atop the ruins of earlier structures. This process has preserved Erbil’s 8,000-year history.

The citadel’s towering walls ring the top of a mound that rises up to 30 meters (nearly 100 feet) above the modern city. Visible from miles away, it is one of the most dramatic sights in the Middle East—a welcome landmark for Silk Road merchants who passed through the region for 1,500 years.

Almost perfectly circular, the citadel has an average diameter of about 400 meters and covers 102,000 square meters. Pottery shards scattered on its steep slopes indicate Neolithic styles, though no conclusive dating has been done. However, some pottery fragments resemble those of the Chalcolithic period and the Uruk and Ubaid cultures of prehistoric Mesopotamia.

For these reasons, Erbil Citadel has often been called the “world’s oldest continuously inhabited site.” On April 2, 2019, NASA recognized it as potentially the oldest continuously occupied human settlement on Earth.

Most of the citadel’s visible structures date to more recent times, particularly the Ottoman era. Viewed from above, the settlement features a unique radial design, a hallmark of late Ottoman urban planning. While the buildings today are just a few centuries old, the land beneath them holds secrets from antiquity.

Locals refer to the citadel as Qelay or Qala’t, meaning “castle.” Surrounded by the sprawling city of Erbil, its height and grandeur can appear diminished, yet it remains a central symbol of local identity. Within the citadel are approximately 322 buildings, closely packed and separated by a web of narrow streets. The area includes palaces, four mosques with towering minarets, and several Ottoman-era bathhouses.

Although the buildings mostly date from the 18th century, the street layout reflects the classic Ottoman style, with winding lanes that all converge at a single entrance: the Grand Gate. This main gateway is flanked by two steep driveways, forming the only access point into the mound.

In the 20th century, the citadel underwent significant changes. Urban development led to the demolition of houses and public structures. In 1924, a 15-meter (49-foot) steel water tank was installed to provide purified water, but it inadvertently caused damage to building foundations due to water seepage.

As the modern city expanded, many residents left the citadel in favor of larger homes with gardens. By 1960, a mosque, a school, and over 60 homes were demolished to make way for a road linking the southern and northern gates. Restoration efforts began in 1979 on parts of the southern gate and the public bath (hammam).

In 2007, the remaining 840 families living in the citadel were relocated as part of a major restoration and preservation initiative. They were compensated financially, though one family was allowed to remain to maintain the site’s claim of continuous habitation. Government plans call for 50 families to eventually return once the citadel is fully restored.

Today, the citadel contains around 500 buildings, many showcasing traditional architectural techniques. Yet it is what lies beneath the surface that may hold the most ancient treasures. The citadel is divided into three main quarters: Topkhana, Saray, and Takia. A walk through the area offers panoramic views of Erbil’s central square—an ideal spot for photography and soaking in history.

Restoration of the Citadel

Erbil’s Citadel holds over 8,000 years of history. Over the centuries, its urban structure has been significantly altered, with numerous houses and public buildings destroyed. Yet in many ways, the Citadel is still growing. Like all tell mounds, continued habitation contributes to its size, age, and archaeological importance.

Today, the Citadel is in a fragile state. Many of its buildings and walls are in urgent need of repair and restoration. Several homes lack basic infrastructure, including proper drainage, electricity, and sanitation. During the 20th century, modern streets were added atop the tell to accommodate car traffic—changes that further damaged this ancient site.

In 2007, the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR) was established to oversee the site’s preservation. That same year, all but one family were relocated to make way for a major restoration project. Since then, international archaeological teams have collaborated with local specialists to carry out research and conservation work.

In 2010, Iraq added the Citadel to its tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage designation, backed by over $13 million in public funding. UNESCO and other international partners have since worked with the HCECR to create a comprehensive preservation and rehabilitation plan.

Restoration has been slow. Decades of civil unrest took a heavy toll on the ancient buildings, many of which still lack electricity and basic utilities. But recent stability in the region has created new opportunities to protect and restore the site.

Today, the Citadel is uninhabited, though museums and souvenir shops have opened. You can even find coffee cups bearing Saddam Hussein’s face, alongside carpets and fridge magnets. In 2004, the Kurdish Textile Museum opened in a beautifully restored mansion in the southeast quarter of the Citadel.

Erbil Today

Each year, millions of tourists—mostly from central and southern Iraq—flock to the Kurdistan Region, with Erbil as their top destination. The region, an autonomous zone within Iraq, has its own government and is home to Kurds, Arabs, Turkmen, Assyrians, Chaldeans and other ethnic groups. Today, Erbil is predominantly Kurdish and known for its rich cultural identity, stunning landscapes, and warm hospitality.

With a population of around half a million, Erbil is Iraq’s fourth-largest city and a major hub of Kurdish life. The densely built city radiates outward from its crown jewel—the Citadel. This towering, walled settlement spans over 10 hectares (about 25 acres), with hundreds of structures closely packed within its ancient walls.

The Citadel is a must-see for any visitor to Erbil. Just below it lies the Qaysaria Market—a maze of shops, stalls, and narrow passageways offering a vivid glimpse into local life.

Wandering through the Citadel’s winding alleys is an adventure. You’ll find cafes, small restaurants, and welcoming locals. Merchants are friendly and never pushy, making for a relaxed shopping experience.

The best times to visit Erbil are from February to May and September to December, when the weather is mild and ideal for walking.

Grand Qaysaria Bazaar

The Qaysaria Quarter and its souk, just across the street from the Citadel, is more than a marketplace—it’s a living time capsule. As you stroll through its narrow lanes, you feel less like a tourist and more like a time traveler.

Dating back to the Ottoman period, the Qaysaria Bazaar is the perfect place to shop for traditional Kurdish clothing, jewelry, and handmade crafts. You’ll also find antiques, including old Iraqi currency—a favorite souvenir for many visitors.

Like many Middle Eastern markets, Qaysaria blends the old with the new. Cellphones and gaming sets sit alongside silver jewelry, daggers, books, embroidered cushions, instruments, lamps, carpets, and fresh produce. Local food vendors serve up kebabs, fresh juices, and traditional sweets.

Gift shops sell beautiful keepsakes, from Kurdish rugs and Persian carpets to jewelry and traditional hats. Exploring the Citadel, the bazaar, and the surrounding markets can easily fill an entire day.

For a break, head to the Castle Café, a whimsical spot that feels straight out of Aladdin. For a more traditional experience, visit Mam Khalil, one of the city’s oldest tea cafes. Covered in vintage photographs, Mam Khalil is a beloved hangout near the bazaar.

Just around the corner, you’ll find the jamadani shop, which sells traditional Kurdish scarves with designs that vary across the region. Nearby is the klash workshop, where artisans craft handmade Kurdish shoes known as gewa. Locals are generally welcoming to photographers, making this a dream for street photography enthusiasts.

Concluding Thoughts

Erbil’s strategic position—between the Zab and Zab Minor rivers, tributaries of the Tigris—has long made it a vital crossroads of civilizations. It also sits at the gateway to the Taurus-Zagros mountain range.

Yet like many ancient sites in Iraq, the Citadel has often been co-opted by modern political narratives. History and archaeology, however, speak for themselves. Erbil’s claim as the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city is hard to dispute.

There’s still much to uncover beneath the surface of the Citadel. Someday, deeper excavations may reveal more secrets hidden in the layers of this ancient mound—echoes from the dawn of human civilization.

Sources: Wikipedia, Unesco, Dr Mónica Palmero Fernández, Erbil Citadel (© Missione Archeologica italiana nel Kurdistan Iracheno/S. Mancini)